By Julia McGee

Former MSNHA graduate assistant

In the summer of 2019, I interned at the Lawrence County Archives, in Moulton–and learned much more than I was prepared for.

To complete the University of North Alabama’s master of arts in public history requirements, I needed 140 internship hours at a credible institution. As I pondered possibilities, I remembered visiting the Lawrence County Archives while I was researching the Women of the MSNHA project. The day I was there, the archivist was relatively new and seemed as if she needed some help. Hoping I’d found the perfect place, I reached out to the archivist, Wendy Hazle–and she was beyond thrilled for me to start as soon as possible.

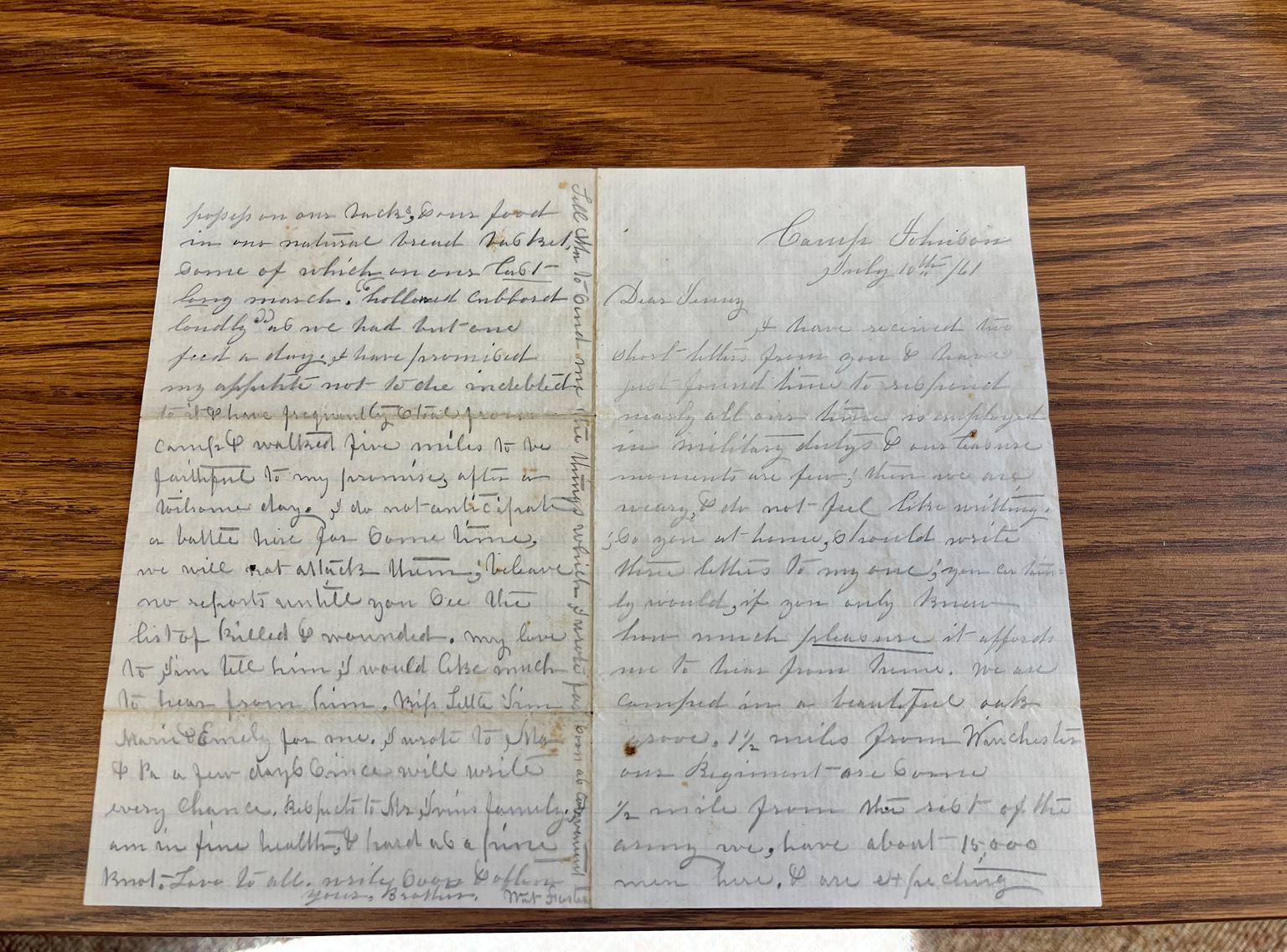

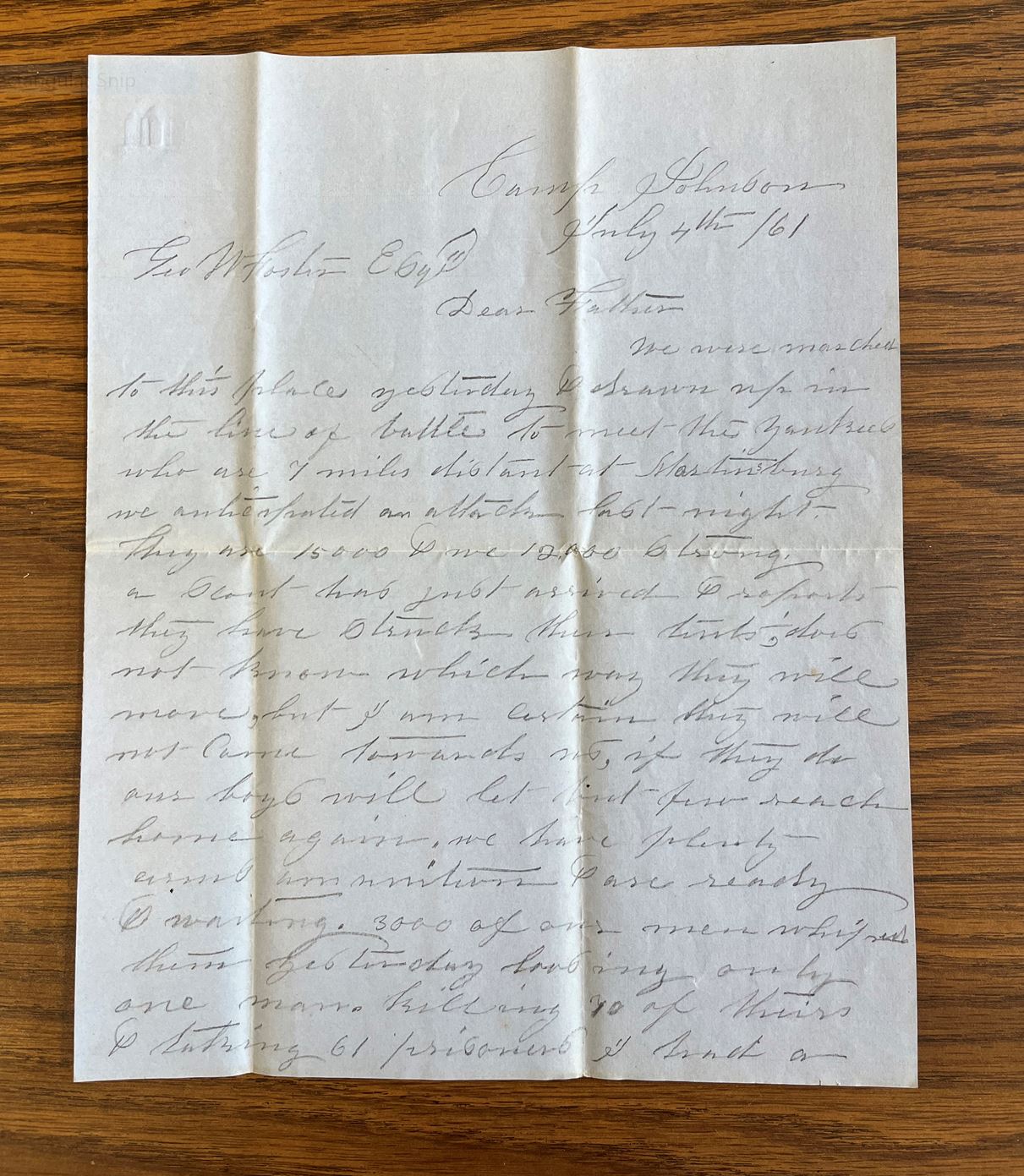

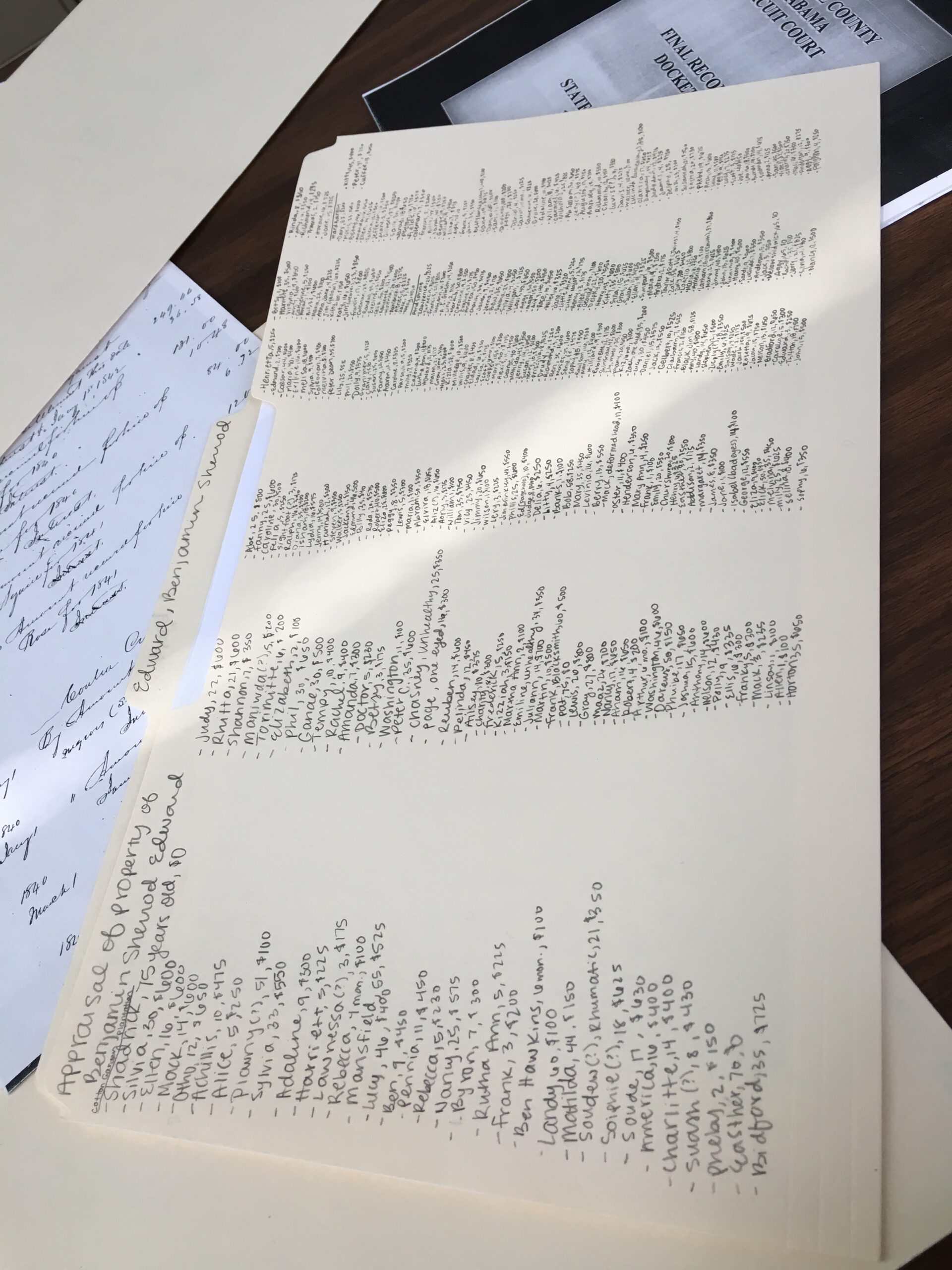

While I often helped with the day-to-day responsibilities of answering phones and helping researchers, my internship task was to build a database of documents on enslaved persons. On my first day I was handed as many unorganized files as I could carry and a box of empty file folders. Each folder was labeled with any names of owners, names and ages of enslaved persons and a single sentence summarizing the document. Over the next month, I completed over 500 folders. The database started as an Excel spreadsheet for the archives’ website designer. When my internship ended in July, the spreadsheet was coming along well. Mrs. Hazle and her volunteers have their work cut out for them to finish it.

I learned more during that month than anyone could have predicted. My skills in paleography (the study of ancient and historical handwriting) and navigating 1800s property records grew. But beyond expanding my professional toolkit, this work expanding my understanding of and empathy for the enslaved. Before beginning the project, I had no idea how emotionally draining it could be. Every file folder either broke my heart or made me furious. The best example of this was a property assessment containing 364 enslaved persons spread over different properties. After creating that file, I realized that the “owner” was only one in a large family of other wealthy property and enslaved-persons owners. As historians, we are constantly interacting with difficult history, but I had never worked this closely with such impactful and challenging history before. It is historians’ jobs to interpret that history for the public, help foster better understanding and insure everyone’s stories are represented.