By Carrie Barske Crawford, Ph.D.

Director, Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area

I grew up in what was once a thriving textile mill town in Connecticut, though by the time I lived there almost all of the mills had shut their doors. The enormous brick buildings with their floor to ceiling windows stood empty, either empty and beginning to crumble or repurposed. The one exception was a mill in the town just north of where I grew up, right over the Massachusetts state line. Cranston Print Works, which had its start in Cranston, Rhode Island, in 1807, only shut down its factory in Webster, Massachusetts, in 2009. Growing up, I didn’t know much about the history of textiles in New England – just that the physical remains on the landscape in my community were evidence of a different time. I drove by signs for the Blackstone Valley National Corridor for years on my way to work in Worchester, Massachusetts, not knowing a) what the Blackstone Valley Corridor was and b) what National Heritage Areas were.

Things changed for me when I was in graduate school at Northeastern in Boston,. For one of my internships, I worked with the local historical society in my hometown of Thompson, Connecticut, on a research project focused on Samuel Slater and the textile revolution in New England. I learned that those huge, crumbling buildings once housed hundreds of workers, producing cloth for the new nation. Slater, who made it out of England with the plans for textile equipment memorized by posing as a common laborer (textile workers were not allowed to leave the country out of fear they would spread the technology and end Britain’s run as the textile capitol of the world), came to the US in 1789. By 1790, the plans he had memorized had been turned into actual machines and the first textile mill in the US was operational in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Slater used children in his factories initially – eventually entire families were employed. Slater went on to build mills in Massachusetts and Connecticut, including the first woolen mill in the nation, which was located in Fabyan – a village in the town I grew up in. Slater’s mills benefitted enormously from the invention of the cotton gin, which enabled enslaved peoples in the South to process a more cotton. This in turn sparked a huge shift in the institution of slavery, which grew dramatically as plantation owners began growing more and more cotton. To do this, they needed more land – and the settlement of the old Southwest, including Alabama, began. The textile industry could not have taken off as it did in New England without the growth of the institution of slavery in the South. While the abolition of slavery in the North did occur at the same time as it expanded in the South, the North continued to benefit from the labor of enslaved men, women and children.

After that summer internship, I didn’t think about textiles much for many years. In fact, it wasn’t until I moved to Florence in 2012 that I became interested in textile history again. As I started to research the history of Florence as part of class projects in my public history classes, I learned that this community, too, had been a textile town. Even before the Civil War, there were textile mills dotting the banks of the creeks that feed into the Tennessee River. The Globe Factory opened in 1839 and it employed 150 people early on. By 1850, the factory produced 80,000 yards of fabric a week, much of it a fabric called “Negro Shirting,” which was a coarse material produced for enslaved people.[1] By 1856, there were three textile factories in Lauderdale County.[2] These factories employed both men and women. At the same time, enslaved people on plantations along the Tennessee River grew cotton for those mills. In 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, there were 139,446 acres of farmland and about 38% (6737 people) of the population of the county was enslaved.[3] While not all of the enslaved people were engaged in cotton production, most were. And some of them may have even worn clothes made from the cotton they planted, harvested and processed.

The Civil War devastated the landscape and the economy of the South, Florence included. During the war, warehouses of cotton were destroyed, rail lines that had once been used to ship both cotton and textiles out of the region ripped up and the enslaved workers who had fueled the cotton economy freed. In the wake of the war, the South struggled to both repair its economy and adjust to the new realties of a society where the color of one’s skin theoretically no longer dictated a condition of enslavement. The economy of Florence slowly recovered, and textiles remained an important part of local business life. Mills, including the Ashcraft Mill and Cherry Cotton Mill, opened in East Florence, which became a thriving industrial community. But while workers enjoyed some amenities, including occasional excursions on the Tennessee River and a baseball team, they worked in poor conditions for long hours and children as young as 12 often joined their parents in the mills.[4]

Top, workers from an Ashcraft Mills baseball team pose for a picture. Above, Ashcraft Mills employees taking a steamboat ride. Both images from UNA Collier Library Archives and Special Collections.

The formerly enslaved men, women and children who had grown the cotton that fueled the textile revolution faced challenges after the war. While some went on to become property owners (especially in western Lauderdale County), many became trapped in a system of sharecropping or tenant farming. Both of these systems created, in essence, a new form of enslavement as farmers quickly became indebted to the owners of the land they farmed in neverending cycles that required them to grow more and more cotton on land that became increasingly worn out and stripped of its nutrients. Poor whites also became sharecroppers – and small farmers, both black and white, continued to grow cotton on their own lands. Cotton gins operated in communities across Lauderdale County and became gathering places as people brought their cotton to be processed.

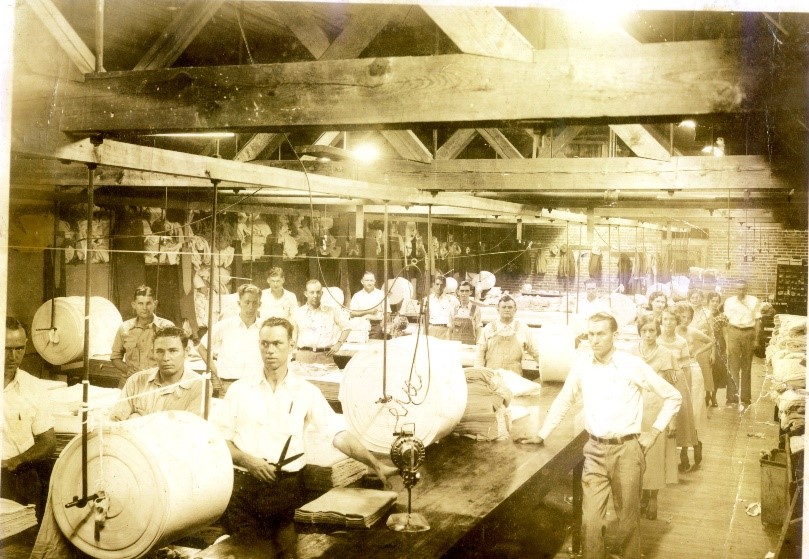

The 20th century brought new challenges and opportunities. Mechanized farming came slowly to Florence and Lauderdale County, with tractors, planters and harvesters gradually replacing human laborers. The boll weevil devastated cotton crops across the South, leading to a mass migration of people out of the region. The Great Depression resulted in the creation of TVA, which helped farmers with fertilizer to restore their worn-out soil, but it also resulted in the dislocation of farm owners and sharecroppers as TVA acquired land to build dams. The textile factories continued to operate in east Florence, producing products including men’s underwear and suspenders. During WWII, the Gardiner Waring Knitting Mill produced underwear for the US Army and Navy.

Employees at Gardiner Waring Knitting Mill stop work for a photograph in 1935. Image from UNA Collier Library Archives and Special Collections.

As the mills in my hometown closed their doors, the textile industry in Florence, Lauderdale County and other places across the Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area thrived. In the 1970s, Lexington Fabrics opened their doors, as did Tee Jays T-shirts. Florence would eventually become known as the “T-shirt capitol of the World.” At the same time, cotton farming techniques changed. The threat of the boll weevil faded as farmers turned to new pesticides and weevil resistant strains of cotton. New equipment made planting and harvesting huge fields with almost no human labor possible. People still picked some smaller plots of cotton by hand but by the late 20th century, that practice, which had shaped life in the South for over two centuries, faded away.

Textiles, too, faded away. By the early 2000s, the factories and mills which had employed thousands in Florence had shuttered their doors. NAFTA and China’s production of cheap textiles spelled the end of American businesses. So, just as in my hometown, the buildings which had housed textile mills came to stand empty, although cotton production continues – drive across Lauderdale County in the fall and see field after field with bales of cotton wrapped in plastic waiting to be picked up. One local business in the MSNHA, Red Land Cotton, grows cotton to produce its own linens and towels and sells those products online and in a retail store, in Moulton. Alabama Chanin and Billy Reid grew a field of organic cotton to try “grown-to-sewn-in-Alabama” products (I have two beautiful shirts that came from this experiment).[6] But, for the most part, the cotton produced here now travels far to be turned into a finished product.

In 2018, Alabama Chanin, the University of Mississippi’s Center for the Study of Southern Culture and the Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area embarked on a partnership called Project Threadways, with the goal of better understanding the textile history of the South. Through the project, I’ve learned even more about the connections between early textiles in the North and the growth of enslavement in the South, the geographic migration of textiles, and how the industry has shaped lives in our country for over 200 years. The Threadways team has conducted oral history interviews with textile factory workers, mill owners, gin operators and workers, cotton buyers and cotton farmers.

One thing that I’ve learned along this twisting and turning path that’s lasted almost a lifetime is that taking the production of textiles for granted is something that most of us do. We are surrounded by textiles – the clothes we wear, the linens we sleep on, the rugs under our feet – but we do not think much about them. However, if we stop and think for a moment, we see a story that involves wars, mass enslavement, small town economics, huge trends in agriculture and architecture and more. So, just for a moment – while you have some free time – think about what you are wearing. Who made it? Where did it come from? What material is it? What will happen to it when you no longer want it? You may be surprised by the answers to some of those questions.

[1] Spirit of the South (Eufaula, Alabama) · 30 Apr 1850, Tue · Page 2.

[2] Sumter County Whig (Livingston, Alabama) · 5 Mar 1856, Wed · Page 1

[3] 1860 Agricultural Census, Lauderdale County, Alabama

[4] Bill McDonald, Remembering Sweetwater, 28.

[5][5] “Mr. Flagg and OPA” Florence Herald, Friday April 12, 1946,

[6][6] To learn more about the project visit: https://journal.alabamachanin.com/2014/09/alabama-cotton/