By Greg Gresham

North Alabama Civil War Round Table

If you’ve ever been in Pope’s Tavern Museum, you might remember seeing an extremely large cannonball, much bigger than anything you will ever see at Shiloh or Corinth, the nearest two Civil War battlefield parks to Florence. It’s often displayed with a small notecard stating essentially that it’s a mortar shell from the USS Lexington, which was at Florence in February 1862 and participated in the battle of Shiloh two months later.

Whoever documented the cannonball’s placard many, many years ago knew the USS Lexington had made a historically significant visit to Florence in February, 1862. The event made headlines in newspapers, North and South, as she and her sister ships swept the Tennessee River clear of Rebel ships from Ft. Henry to the Muscle Shoals. But, most likely, this isn’t a cannonball from that ship. The Lexington’s normal armament was six cannons: four 8-inch Dahlgren guns and two 32-pounder guns. The 8-inch Dahlgren guns are large guns, considerably larger than the 2.6-to-4.6-inch guns firing 6-to-20 lb. shells seen on Civil War battlefields. Guns of this size needed a “stoutly” sized ship to support them, and the Lexington was larger than most steamboats — being timber-clad, she displaced over 450 tons.

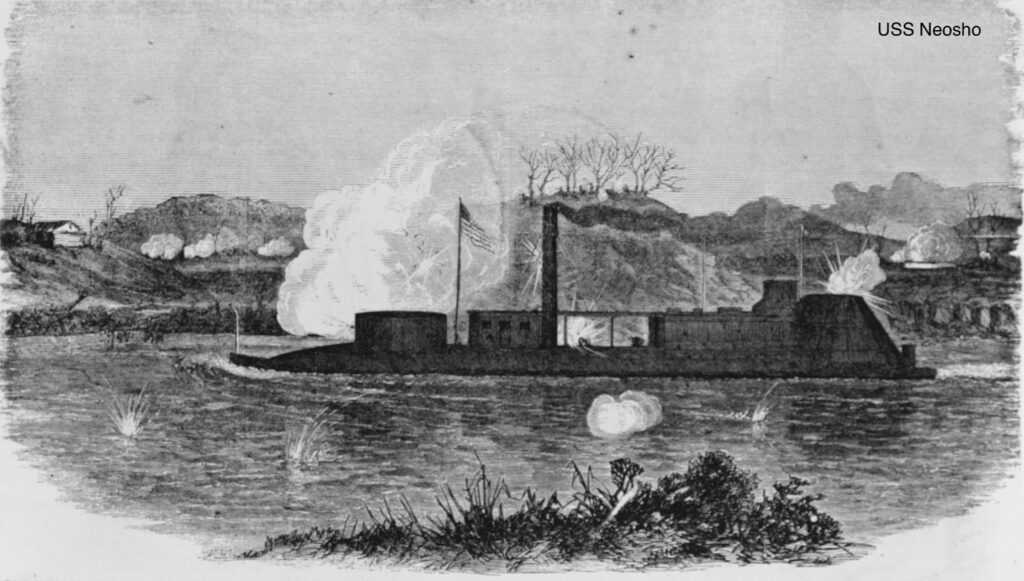

However, the Pope’s Tavern cannonball is larger than an 8-inch Dahlgren shell and hence its designation as a mortal shell. But if it were a mortar shell, the gun that fired it would still need a ship larger than the Lexington to support its gun. Riverine gunboats that could support guns of this size were typically ironclads, such as the USS Cairo, which is on display at the Vicksburg National Battlefield Park. These Ironclads displaced over 500 tons and their main armament was multiple 11-inch Dahlgren guns. The Pope Tavern’s cannonball’s diameter and weight is a perfect match for being fired from an 11-inch Dahlgren gun. So which ship or ships came to Florence armed with 11-inch Dahlgren guns? Just one: an engineering novelty — the ironclad USS Neosho.

But every museum object should have a story. Perhaps that is why the cannonball has been attached to the Lexington for so long. To unravel the history of this story, let’s start with a passage from a column called “Random Ramblings” written in April 10, 1908, issue of the Florence Times-Daily:

…..December 24, Christmas Eve, the federal gunboats made their appearance here to intercept Hood’s retreat, but the confederate pontoon bridge was laid at Bainbridge and the major part of the retreating army had passed over to the south side. The gunboats tendered the city the season’s greetings in shape of bombshells of washpot size during the afternoon. The confederates sent a two-gun battery from Bainbridge late in the evening which was placed in position during the night. Early on Sunday morning (Christmas day) Col. Josiah Patterson with his regiment of cavalry was sent to support the guns. The boats shelled the entire territory within range of their guns for two hours and then turned their attention to the guns on the shore, which were soon put out of commission, after which one boat proceeded up the river to within range of the confederate bridge to which it did considerable damage. The boat was opposed by one brass gun whose every shot struck the boat but did no damage. The boats withdrew—the last guns of the war having been fired in this section. Hood continued his retreat south, the pontoon train followed as far as Nauvoo, where a federal cavalry command which dashed out of Mississippi, captured and destroyed it with the wagons. If the people had felt hard times before they were now confronted by absolute destitution–and bitter despair which fell to the lot of no particular person nor condition. But let it pass.

The war ended, men came home, men who wore the blue and men who wore the gray—men of unswervable principle—they proceeded as best they could to repair the desolation wrought in their contention, avoiding the evil “troublous spirits” tried to provoke. Their work was slow, but the efforts of those cool, conservative men has borne and is bearing fruit that is an everlasting monuments to their worth as men.

The Bohemian has been complimented exceeding recently by readers of his “rambles” both by “Blue” and “Gray.” I have refrained from referring to incidents that engendered bitterness on either side. Few of us who were in the disputed territory—no matter where our sentiments ranged—but had experiences that left bitter, undying remembrances. It is sadly so, and sad it is so.

And with it all Florence is a growing town with some of its old time citizens yet remaining, but they, like the veterans, are passing—passing.

The Bohemian.

The Bohemian, a pen name for a writer who was a child during Florence’s years during the Civil War, often talked about history in his columns. In fact, in his first column the Bohemian discussed how important it was to place historical markers about the town:

Few towns, if any, in the State have as many points of historical interests as Florence, and not one of them is marked so the passing stranger may know them.

The Bohemian had a few minor inaccuracies in his column about the gunboats, but the accuracy is remarkable compared to primary documents related to the time that said “federal gunboats made their appearance here to intercept Hood’s retreat.” Remembering the town’s history was important to the Bohemian. Perhaps the first “newspaper historian” of the area, he often wrote about the Civil War & included gunboats a couple of times. As a side note, his family was pro-Union & suffered much during the war, which explains his comments at the end of his column.

So that is one story to attach to this cannonball. Another is a painting by artist & author Kurt Vetters, who also has been a Civil War reenactor. I’ve attached a sketch by Vetters that shows the USS Neosho engaging two Confederate artillery pieces near the railroad bridge. Another Confederate gun in in the picture, on Todd’s hill in the distance, alongside a Civil War Florence. The ship positions and the artillery positions are based on reminisces from the fighting in December, 1864.

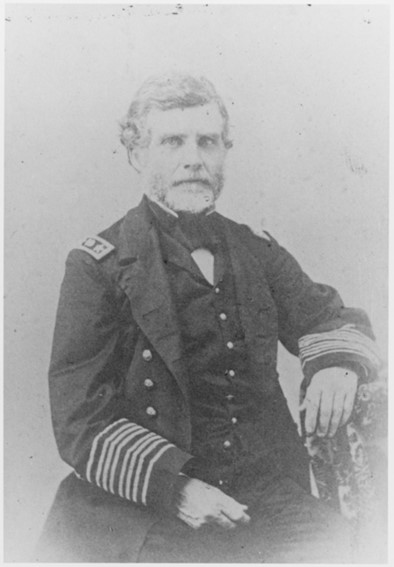

Adm. Samuel Phillips Lee, who led the ironclad USS Neosho, tinclads USS Reindeer and USS Fairy in the battle Vetters depicted (left), wrote the following telegram to Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles after the battle:

Flag Ship Fairy, Chickasaw Ala, Dec. 27th, 1864

Hon. Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy:

I have destroyed a new fort at this point, and all the enemy’s visible means of crossing the Tennessee below Florence, and today blew up two caissons and destroyed two field pieces there knocking one into the river, the other into pieces.

The battle did not go without casualties — two unknown Civil War graves were unearthed around South Wood Avenue during construction around the early 1900s. The Bohemian identified them as Confederate soldiers who had manned those field pieces at the water’s edge. Union newspaper accounts mentioned three men killed on the gunboats, possibly due to Rebel sharpshooter fire from the south bank of the river.

One last note: The USS Neosho, along with its sister ship the USS Osage, were unique vessels for the Union Navy. The Neosho was designed to be shallow draft ironclad, having under 4 feet of draft so it could travel shallow & shoal-filled rivers. It could go where many tinclads couldn’t go. All other ironclads had drafts of over 6 feet and, on the Tennessee River, could never pass over the Colbert Shoals to reach Florence. The Neosho played an important role in alleviating the river blockade of Nashville in early December 1864 by passing over the Harpeth Shoals. But at Florence, its pilot, according to Adm. Lee, refused to take the ship on the Little Muscle Shoals. This may have resulted in the destruction of Hood’s pontoon bridge. Amazingly, Lee corresponded with engineer George Washington Goethals while Goethals was working on the Muscle Shoals Canal in 1892 about the fundamental details of the Muscle Shoals. Lee seemingly wanted to understand if it had been possible or not for the Neosho to get within range of the pontoon bridge.

Goethals responded to Lee’s questions noting velocities at low & high stages of water. Lee would have been interested when the New York-born Goethals noted that, at the lower extremity of Forty Acre Island, water velocities approached 5.3 miles per hour — this was the point in which Lee’s ships came closest to the Confederate pontoon bridge at the Bainbridge Eddy. The engineer gave Lee data about the river gauge located on the railroad piers and later said that it was originally built for railroad purposes only, as the State charter under which it was constructed did not provide for any means to allow of the passage of boats; Florence at that time was considered the head of navigation. Lee was prepared to use that final comment to defend his failure to destroy the bridge.

So, if you get a chance, take time to go by Pope’s Tavern and see that 140-lb.-or-so cannonball. Then ride down to the park under O’Neal Bridge and gaze out towards the Old Railroad Bridge piers. Imagine a Confederate artillery position nearby and visualize the USS Neosho chugging in the stream, its engines struggling to push its 523-ton, 180-ft.-length into the current. Now, remember that Few towns, if any, in the State have as many points of historical interests as Florence.