By Greg Gresham

North Alabama Civil War Roundtable

Please read the Part No. 1 post for background on “The man labelled as P–.”

Normally it’s almost impossible to determine the real name of a person who is identified with only one letter. For some reason “Z and Zorro” comes to my mind as an example. This tale, while having some similarities, isn’t the same. There are some facts and assumptions that might lead us to some possibilities of who P– was. (Let’s call him “P” from here on). And even if we don’t definitively find or prove who he might be, following the path of circumstantial evidence often leads to interesting stories by themselves — no matter if the person is a perfect fit for the deeds told in DeForrest Hyde’s narrative.

Reviewing Hyde’s article, it’s easy to conclude that “F–” stands for Florence as we know that Hyde was a lifelong native of Lauderdale County. We’ve also made an educated guess that the Bluewater Creek watershed is the most likely area depicted in Hyde’s story. Another logical assumption would be that when looking for P, the letter P stands for the first letter of the man’s last name. Those assumptions and the key fact given that the man “was a soldier in Lee’s army” leads to an interesting potential fit.

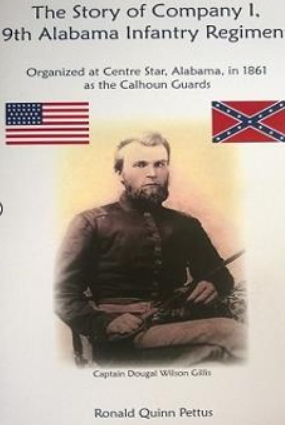

Three companies of Lauderdale County soldiers were in Lee’s army during the Civil War: Companies D and I of the 9th Alabama Infantry and Company H of the 4th Alabama Infantry. Just a handful of soldiers’ last name begin with “P.” In the area where we’ve placed Hyde’s story, a significant number of soldiers enlisted in the Calhoun Guards, which later became Company I of the 9th Alabama.

Local historian Ronald Quinn Pettus’ book “The Story of Company I, 9th Alabama Infantry Regiment” gave interesting facts about a Pettus family related to the author’s ancestors.

According to Ronald Pettus, Private Pettus’s mother became a widow when her husband, Horatio Overton Pettus, was found hanged on August 29, 1864. Hyde’s story took place in early 1865, so this hanging was a fairly recent event. The Pettus family, as passed down in oral history, assumed that the Union troops committed the transgression. Pettus told me there was no definitive proof who had hanged the elder Pettus, so it may have seemed logical to the family that patrolling Yankee cavalry were the culprits — Union cavalry patrols at that time were executing any male of military age suspected of being a guerilla, bushwhacker, or thief practically on the spot, utilizing the so-called drum-head court martial.

Just two weeks prior to Pettus’ death, for example, soldiers of the 10th & 12th Tennessee Cavalry under the command of Col. George Spalding shot a man named Andrew Blakemore in nearby Lawrence County, Tennessee. Spalding said that Blakemore was a guerilla, but soldiers in his command later said they thought Blakemore was a thief. Regardless, men were arrested one day and shot the next. But the key here is that Blakemore was shot and not hanged — hangings were usually carried out in town squares or military camps. Executions in the field were almost always carried out by firing squads.

So at the start of 1865 the widowed mother was left with three sons. The two oldest, George David (26 years old) and Winston Corneilus Pettus (24 years old), were in Company I of the 9th Alabama Infantry, in Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. A younger son, a soon to be 12-year-old William Washington Pettus, lived at home with his mother.

Thus, we have a family who could fit Hyde’s narrative: soldiers who served in Virginia, a widowed mother, and a motive for revenge if the father was hanged by a rogue outlaw band instead of the Yankee army. The question is which of the two older brothers was potentially P?

The younger of the two, Winston Corneilus, would not live long enough to be P. I’m going to make a slight detour from the story line to discuss the Pettus soldier’s situation via a family letter. In early 1864, over a year prior to Hyde’s narrative, Winston Pettus was in camp in Virginia. Knowing that the Union Army would soon advance toward Richmond, he wrote the following words to his father in January of 1864.

(The letter is as written; many words are misspelled. The “….” Between words indicate illegible words, or missing words due to paper damage, etc.)

January the 5th, 1864

Campt Near orange cout house, Va

Dear father and mother

I once more seat myself to write you a few lines to let you know how I am getting along I am well at this time hoping when these few lines come to reach you they will find you all ……. well far I have not been able to rite to you we had a fine snow years end. Last night we ……… when it cum new snow ……… men deserting by wholesale near every day they was searching this company last night and I can tell you a great menny more will leave before next spring if they don’t get to furloughing ther men better …… men left company ………. morning they went across the river to get their breakfast and went to the Yankes I want ….. to get to cum home…… think I will be staying awhile so whatever will far I am as tired of the war as enny boddy Aught to be. I would be glad to be there but I don’t now whether I will Ever hav the opportunity of seeing home Again in this life but I hope it will not be long before the war wil cum to A close I am Afeared the yanks has left you nothing to go Apon. I hope that I will get to come home before long but I don’t see no chance to get off. I would be glad to hear from You once more. I wont you to right whare George Is and what he is doing if you now. I don’t think we will have Enny more fighting to do hear before spring then we will have a hard time then if the Army don’t All desert before that time they will be A great menny cum before them this army is getting nier out of heart than I ever saw them. This regiment will disband jest as sune as ther times is out. Ouer time will be out in June if they don’t take to Furloughing more for they will leave by the holsale if they don’t get to go before …… this war by spring I think the men and for they will leave so fast it will make ther heads swim so I will bring my letter to A close by saying I still remain your effectionate son. I will quit for this time and right Again sune so good by for this time well billy I will rite to you and henry will billy I would be glad to see you and henry when I cum. I will bring you some thing but I don’t now how long it will be before I get…to cum you must be a smart boy and rite to me how you are getting Along you must break charles if the yankes ant carried him off tell becky that I will fetch her a fine bonnet when I cum if I don’t for get it and ever get to cum well billy I hav nothing neu to rite to you so I will quit for this time so good by for this time

W. C. Pettus to H. P. Pettus

The letter exudes Pettus’s overwhelming homesickness and desperation for a furlough. He asks his father about his brother George’s whereabouts. Records show that George Pettus had been granted a furlough but hadn’t returned to the unit. At this point in the war, Confederate desertions had become a major problem, and Winston’s letter confirms that issue. He also addresses his younger brother William as “Billy” and wants him to break a horse, perhaps with his first cousin Henry’s help. Becky, to whom Winston Pettus promises a bonnet, is his sister.

On October 26, 1864, just a few weeks before turning 24, Winston Pettus finally got a furlough to come home for 60 days. Perhaps it was granted because of his father’s recent death. He was able to make it home and evaded capture by the Yankees when Hood’s Army retreated from north Alabama in December 1864. According to family history, he contracted measles and died on March 11, 1865.

With Winston Pettus dying in March, George Pettus is likely the revengeful soldier in Hyde’s story. Perhaps he discovered or assumed that the outlaws mentioned in Hyde’s narrative killed his father. Or perhaps it was as simple as Hyde said: “(the) gang went to the (Pettus) house, took the horse, and abused the old mother;” That alone might have motivated revenge. If George Pettus were P, one may conclude he may have become remorseful – Hyde said his column that the man he was talking about “found the Lord” around1868 (shortly after these events). George Pettus reportedly lived the final 42 years of his life under “the guiding hand of a loving God.” He died at the age 72 in 1911.

So ends the story to find P. What do you think?

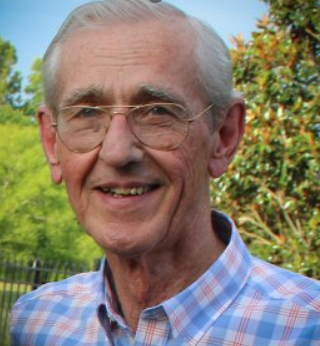

Winston Pettus’ letter and other detailed information about Lauderdale County soldiers are in Ronald’s Pettus’ book noted earlier. It’s as good a book as we have on our local history.

Ronald Pettus was a well-loved and respected high school history teacher as well as a locally renowned author. He recently passed away, and the last interaction we has was when I shared the Hyde story with him and discussed how possible it might be that George Pettus was the revengeful soldier of Hyde’s story. In the end, we agreed that we probably would never discover the absolute truth of such a story — in particular one that is imperfectly documented — but the search, the journey that one travels in the attempt at the truth, usually leads to another tale.