By Greg Gresham

North Alabama Civil War Round Table

Recently, I wrote a couple of Civil War era articles about the “Hidden Ford” on Shoal Creek. Though the combat described in the article was essentially a widespread skirmish, it could have been a bloodbath as an outnumbered Union cavalry brigade fought a series of delaying actions, while being pushed back towards a swift running and swollen Shoal Creek. If you haven’t read those two articles, you can find them here & here.

There is a loose end that I didn’t tie up in those two articles. It’s an interesting story related to the Union battalion, some 200 soldiers of the 9th Illinois Cavalry commanded by Capt. Anthony Ritenour Mock sent to reconnoiter the Waynesboro Road (known today as the “Chisholm Highway”). Col. Datus E. Coon, the commander of the Union cavalry brigade in which the 9th Illinois belonged, reported Mock’s journey that day as follows:

“He (Mock) succeeded in reaching the Waynesborough road, but in returning found himself and command completely surrounded by the enemy, and took to the hills by meandering neighborhood roads. By accident he came upon General Chalmers’ division wagon train and made a charge on the guard, capturing several wagons and prisoners and fifty mules, besides much plunder which he could not bring away. While in the act of destroying the train he was attacked by a superior force and compelled to leave all and take to the woods again. By the assistance of Union men and negroes he was guided by circuitous routes until he reached the column. His loss was thirty men, most of whom were taken prisoners. Papers conveying important information were captured with the train, information which must have been of infinite importance to General Thomas, as they detailed the movements about to be made, giving timely notice to all of what was to take place. Captain Mock is entitled to much credit for the skill displayed in bringing out his command with so little loss.”

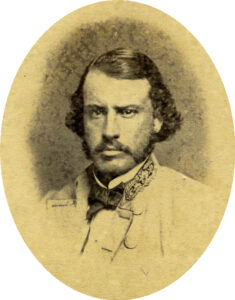

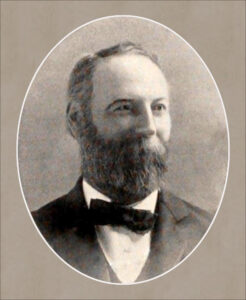

At the time of this incident — Nov. 19, 1864 – Mock, 28, was in command of a battalion in the 9th Illinois Cavalry. He was born in Illinois and spent his childhood years there. After learning law in Indiana, he eventually migrated to Missouri. He found a teaching position there shortly before the outbreak of hostilities but apparently had a tough time getting out of Missouri and back to Illinois to enlist as he was a “known Union Man.” He was made a sergeant in his company shortly after enlisting in 1861. His leadership qualities, in camp and in battle, meant he rose rapidly in the ranks, becoming a captain on June 11, 1863. A few days later, he received praise again from his brigade and division commanders for his rear-guard heroics at the battle of Campbellsville, Tennessee during the Confederate move northward into middle Tennessee. His battlefield performances led to promotions to major and later to lieutenant colonel of his regiment. After the war, Mock practiced law in his native Illinois, eventually becoming “Judge Anthony Mock.” He died in 1899 at the age of 62, with his tombstone denoting his title as a “Lt. Col.” rather than “Judge.” We are indebted to Mock for details on the capture of those “important Rebel dispatches” and his command’s perilous escape from Confederate cavalry due to the narrative he gave 9th Illinois Cavalry’s official historians.

These historians, who published the 9th Illinois Cavalry’s history , obviously thought that Mock’s escape from certain capture was vital at the time as they asked him to write down the details. Years later in “The National Tribune” — which documented several first-hand experiences of the common soldier during the war — many of Gen. John Porter Hatch’s cavalrymen said that the information Mock brought back to the division was vitally important in the upcoming military campaign that culminated in the battles at Franklin & Nashville.

So, first, let’s go over Mock’s description of what happened that day and night. Second, we’ll review just how important that dispatch might have been for the Union army. I’ll add some Confederate memoirs for additional perspective. My comments are in parenthesis to add clarification as needed.

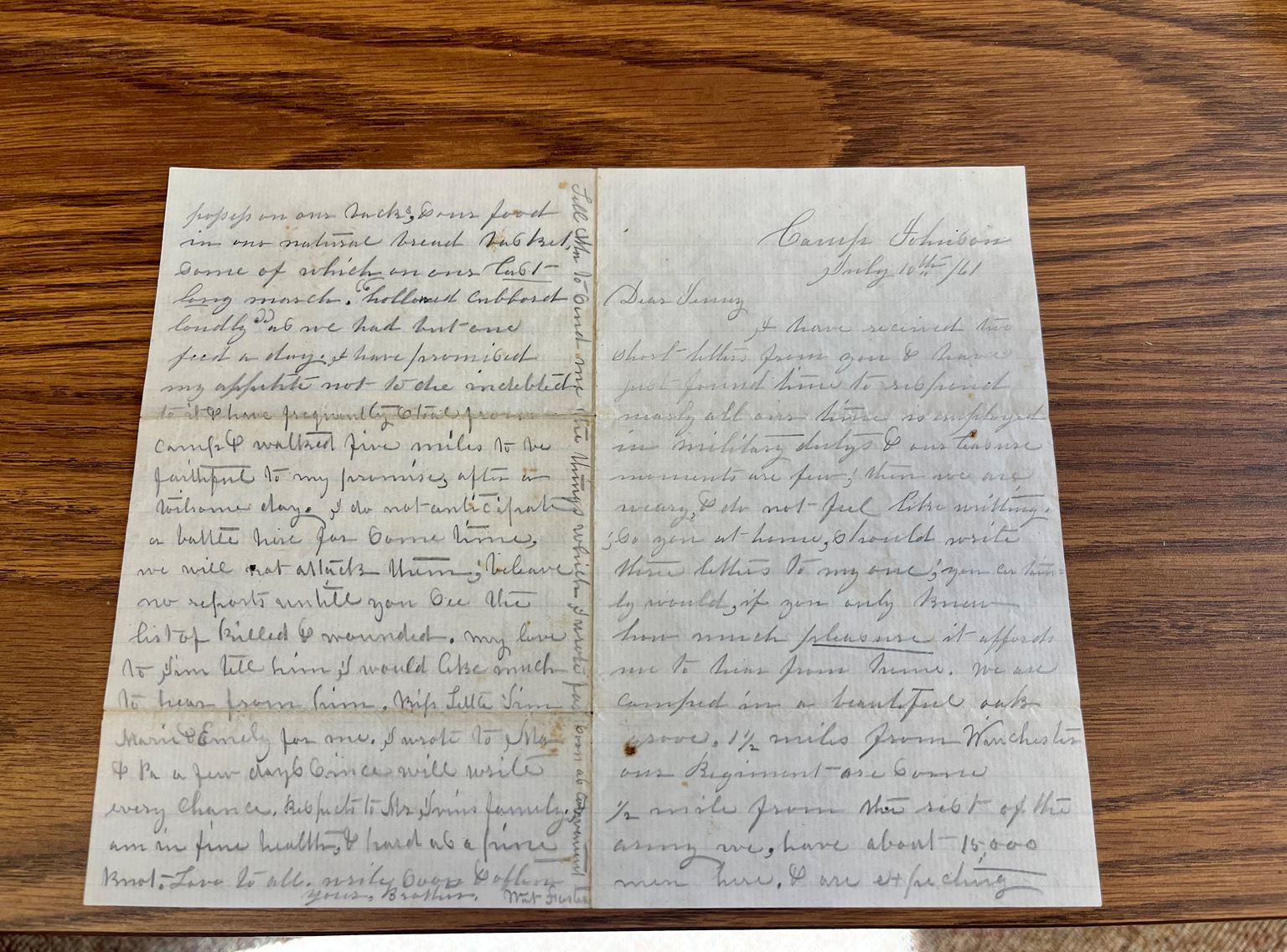

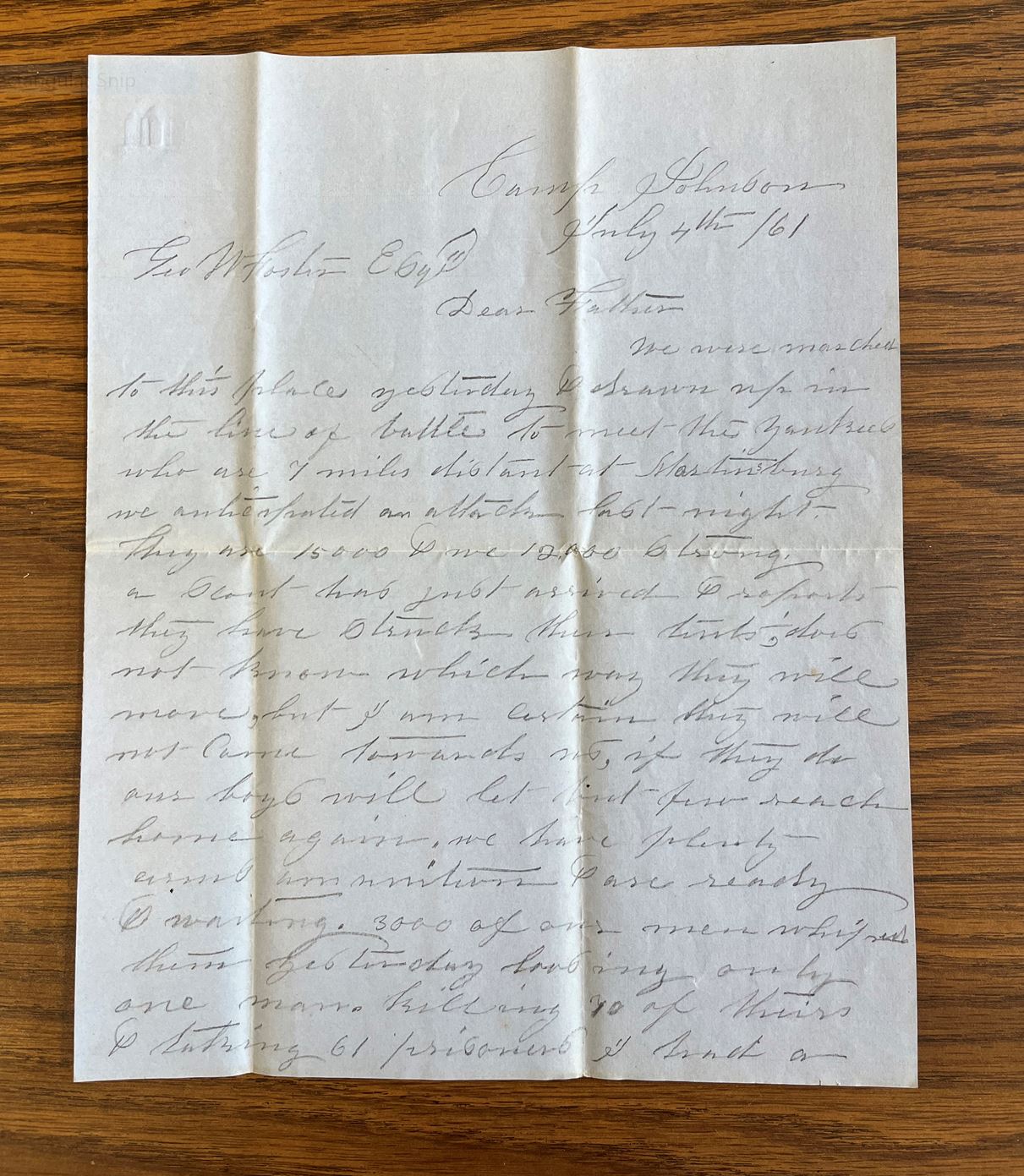

Back to Mock’s report:

On the morning of November 19, 1864, in order to ascertain the strength of the enemy on the south side of Shoal Creek, and north of the Tennessee River, General Hatch ordered the Second Brigade to move to the ford at Cowpen Mills and cross Shoal Creek, and go into camp at or near Bailey’s Springs, on Butler Creek. Shoal Creek was a stream fully one hundred yards wide, with an uneven, rocky bottom, and only ford able at certain places. (The spring on Butler Creek is near Pruitton. Calling it “Bailey Spring” is an error — the actual Bailey Springs was nearer to Florence. Shoal Creek divided the forces east/west and not north/south, which I’ll comment more on later. There had been almost non-stop rain in the area for three weeks. You couldn’t cross Shoal Creek except at a high-water ford during this time.)

The 9th Illinois Cavalry, Capt. (Joseph W.) Harper commanding, was in the advance, and Captain Mock’s Battalion, the advance guard of the Regiment. Soon after crossing the river we struck the rebel pickets, and drove them back as we moved forward. Two and one-half miles from the river, we came to a cross road. (County Roads 8 and 61)

Here our command was to turn to the right and march to Butler Creek. On reaching this cross road, Company L, Captain J. H. Carpenter commanding, was placed on the cross road leading to the right, as a picket, and to protect that flank while the command was passing. Captain Carpenter then, with his company, moved forward on this road, about one mile, and, hearing the sound of moving wagons and artillery but a short distance over the hill, became convinced that the rebels were there in force, and marched back to his picket post. (Company L moved left, not right, and south along County Road 61, i.e. The Butler Creek Road. The main command had moved right and north on Butler Creek Road. The Confederates that they are hearing are cavalry units near Indian Camp Creek who broke camp earlier in the day and moved northward in preparation for moving into Tennessee on Nov. 21.)

They had not been stationed here long, when they saw a solitary horseman approaching on the road. The timber was scattering. He seemed to be quite unconcerned, and entirely unaware that there were any Yankees over the river (Shoal Creek); when he came within two hundred yards, John Shelton, against the order of Captain Carpenter, fired at him, and he immediately went back and over the hill ; soon the rebels began to appear over the crest of the hill, and Captain Carpenter sent a courier, Henry Shelton, to Captain Harper, informing him of the state of affairs, and asking for orders. Captain Harper, realizing the situation, ordered Captain Carpenter to fire a volley if attacked, and hold the enemy in check as long as possible, and then moved to his relief with the balance of the regiment that was left with him. In the meantime the rebs kept coming up over the hill, and moving forward toward the picket. Captain Carpenter threw his company into position to receive them, by dismounting his men and forming them in a half circle behind the trees, and awaited the coming charge of the rebels, with instructions to his men not to fire till he gave the order. The rebs charged up, and when within short range Company L opened on them from their seven-shooting carbines, and kept up a stream of firing; on dashed the rebels into and through the little band. Many horses were shot and rebels killed. A prisoner captured the next day reported that they lost sixteen men killed, and supposed they were fighting a brigade. One rebel’s horse fell, shot through the neck, at Captain Carpenter’s feet, and his two revolvers dropped from his saddle, which Carpenter picked up. The Johnnies could not stand the fire and retreated, while Company L did not lose a man. It was bravely done. How in the world this one company beat off at least two hundred rebels was a matter of surprise. When Colonel Coon inquired who was on this picket, and was informed that it was Captain Carpenter, he said, “It was all right, and he felt safe.” Pretty soon Captain Harper came up, and the rebels came back again, this time in larger force, and, after a sharp fight, our whole command was driven over the river (Shoal Creek).

The Confederate column that attacked the Federal troopers, at the crossroads of CR8 and CR 61, were the lead elements of Gen. Frank Armstrong’s Brigade, who had been ordered to new positions northward in preparation of the Confederate advance into middle Tennessee. A Rebel trooper in Armstrong’s Brigade, 21-year-old John Greer Deupree, a member of the Noxubee Squadron (Company G), of the 1st Mississippi Cavalry Regiment, and later a prominent faculty member at the University of Mississippi, remembered a skirmish that took place while the company was watching the Union Cavalry along Shoal Creek.

… Captain King of the Noxubee Cavalry, who had long entertained a presentiment that he would be killed, while riding at the head of his company and leading the advance of Armstrong’s brigade, was struck centrally in the forehead by a minie-ball and instantly killed, to the utter amazement of all. No one was apprehensive of danger, not an enemy was in sight, and no firing was heard in any direction. We were ascending a hill but could not yet see over it. Evidently, the ball had been fired by a Federal sharpshooter from a long-range gun and was on its descending trajectory when it struck Captain King. King’s presentiment like that of Bealle previously mentioned in this narrative was thus realized. His death was deeply lamented, for he was universally popular. First Lieutenant T. J. Deupree (J.G.’s brother) from this time till the end of the war commanded the Noxubee Cavalry. After mounting the hill and advancing more than a mile, we discovered the enemy’s line, and a brief but sharp skirmish followed, in which among the first to fall was Lieutenant Henley of the Noxubee Troopers. Thus in less than an hour our Squadron lost two of the best officers we ever had

The description that the Mississippian trooper gives makes one wonder if his column wasn’t the attacking Confederate force at the crossroads. Indeed, “a brief, but sharp skirmish” with several Rebel troopers falling at the crossroad would appear to match both stories. Perhaps the bullet fired by “John Shelton,” mentioned in the Illinoisan narrative, which obviously missed the “solitary horseman,” went onward to descend over the hill and strike Captain King. Re-reading the Illinois narrative, the timing of the events could have been reconstructed slightly in error, as most of these regimental histories draw on numerous accounts from different soldiers. The initial picket post, a mile south of the intersection, most likely was where Shelton fired his rifle, rather than at the crossroads. Then the unit saw Confederate horsemen come over the ridge, thus causing the retreat back to the crossroads. If the events were perfectly stated in the Union account, it’s hard to imagine that the ambush could have been set up while Confederate forces were coming into view.

As we discussed in the “Hidden Ford” articles, the Union troops lost control of the CR8 and CR61 crossroad and the bulk of the brigade was driven across Shoal Creek, finding & utilizing an obscure ford as an escape route.

This leaves Mock’s little battalion cut off from their brigade, essentially in the middle of 4,000-5,000 Confederate horsemen marching northward. In Part II, we’ll find that Mock’s cavalrymen have some initial success in their movement towards the Waynesboro Road, but the battalion’s good fortunes does not last long.

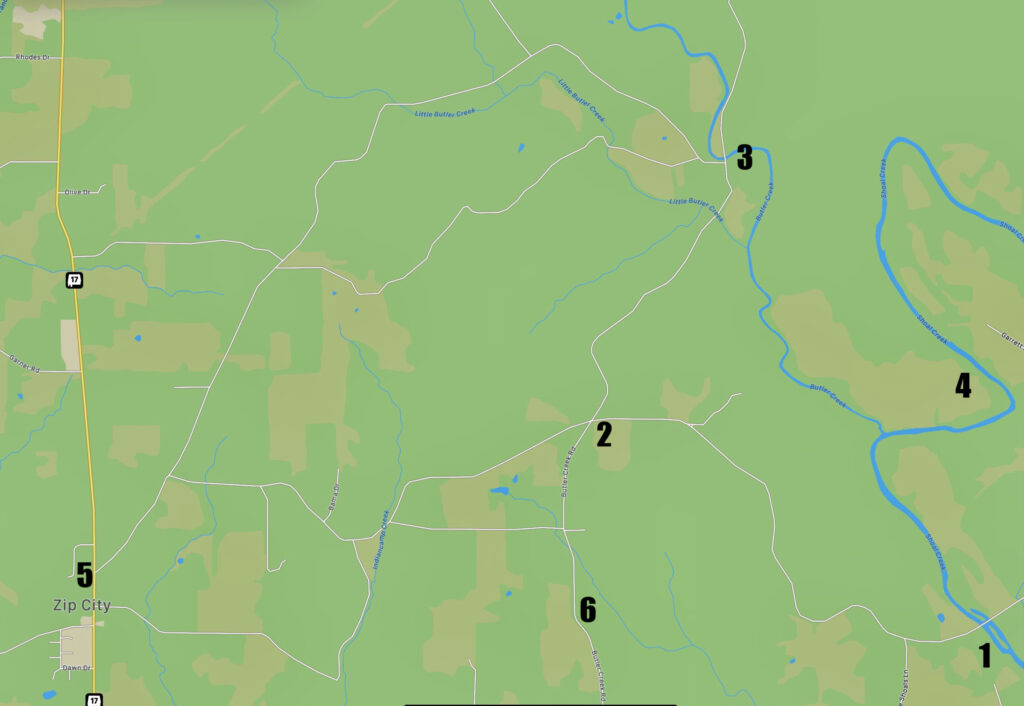

Here’s a Lauderdale County area map showing the area of operation on Nov. 19, 1864. Shoal Creek is on the right & Butler Creek flows southeastwardly from the north. See below for map key.

1. – Cowpen Ford, current-day Goose Shoals crossing of Shoal Creek on County Road 8.

2 – Intersection of county roads 8 & 61. CR61 is also known as the Butler Creek Road. Armstong’s Confederate cavalry brigade, with some loss, drove Union forces from the crossroads.

3 – Area on Butler Creek where Coon’s Union brigade intended to encamp, but Confederate Col. Edward Crossland’s Kentucky cavalry brigade was already there.

4 – Location of the “Hidden Ford” across Shoal Creek, a fortuitous escape route for Coon’s brigade.

5 – Destination for Mock’s battalion. His goal was to find the Union cavalry operation from Waynesboro near here. Instead, he ran into Gen. James Chalmers’ rebel cavalry division.

6 – Area one mile south of the CR8 & CR61 crossroads, where the initial Union picket post was set up. Just south of that point is potentially where Capt. James King was killed, riding at the head of his troops.