By Greg Gresham

North Alabama Civil War Round Table

On June 6, 1895, one Henry Newton Pharr sat down in his home at Lagrange, Arkansas, to write a tribute to a recently departed friend & fellow engineer Robert Linah Cobb. He had learned of Cobb’s death in the June 4 issue of the Memphis Commercial Appeal. The obituary was a simple one, pared down substantially from Cobb’s hometown paper, and had run in several large subscription papers in the South, including Memphis, St. Louis, Nashville & New Orleans. It appeared in those cities as follows:

subscription papers in the South, including Memphis, St. Louis, Nashville & New Orleans. It appeared in those cities as follows:

Capt R L Cobb

Nashville, Tenn June 3 — Capt. R. L. Cobb chief engineer of the Ohio & Southwestern Railroad with headquarters at Cleveland O., died yesterday at Clarksville, Tenn. aged 54 years. He was one of the ablest civil engineers in the South, and for many years was in charge of the construction department of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad.

Pharr had decided that this short two-sentence blurb, wasn’t good enough for his old friend and began writing.

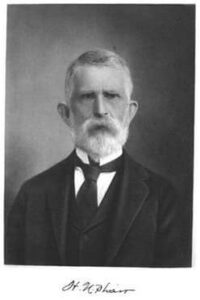

Cobb and Pharr both served in the Confederate Engineering Corps during the Civil War. They served together at Ft. Donelson, both evading capture somehow when the post surrendered in February 1862. Cobb was later wounded at Shiloh. Eventually, both would become captains commanding engineering companies. They surrendered together, with the rest of the Army of Tennessee in North Carolina, on May 9, 1865. After the war, they both worked on railroads, and evidence suggests they may have had some association at that time. Capt. Pharr left his railroad career behind at some point, returning closer to his pre-war home in Arkansas to work on levee construction & making quite a reputation doing it. Though their travels had separated the two Confederate comrades at some point in their later life, Pharr had not forgotten the deed his friend had done on Christmas Day, 1864, and his letter appeared in the June 7, 1895, issue of the Memphis Commercial Appeal as follows:

A TRIBUTE TO A HERO

How Capt. R. L. Cobb Saved the Army of the Tennessee.

LaGrange, Ark., June 6, 1895.

To the Editor of The Commercial Appeal:

Your issue of yesterday tells us that R. L. Cobb, late captain of engineers, C. S. A., is dead at his old family home at Clarksville, Tenn.

To the few, very few, of his comrades of the corps of engineers of the Army of Tennessee whom he leaves behind, that little paragraph brings a volume of regrets and revives memories that had almost perished the cares and struggles of thirty years of life such as none but Southern beneath men have lived or can appreciate.

These memories recall one incident in the history of the Army of Tennessee which come within the knowledge of but few and did not find its way into official reports, and which I now wish to put on record as tribute to his memory.

Capt. Cobb was the junior captain and the youngest man of that rank in the corps. He was a man of courage

and intelligent enterprise, of many agreeable traits of character, a high sense of honor and faults enough to make one like him. Early in 1863 the Third Regiment of engineer troop was organized by detailing from each division of the army one company of expert mechanics of 102 men. These companies were offieered by assignments from corps of engineers and two of these companies were organized into a corps of pontooniers and furnished with a train of boats (right) and bridge material. Capt. Cobb was assigned to one of these as junior captain of pontooniers.

After the battle of Chickamauga the senior captain of the regiment with one battalion was sent with Longstreet to help him into Virginia. Six companies remained with the Army of Tennessee. Our field officers were attached to the personal staff of the army and corps commanders, our colonel being chief engineer of the army. I as senior captain of the six companies commanded the battalion.

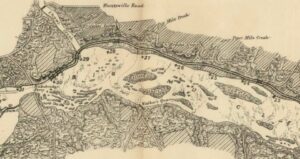

While our pontoon outfit was sufficient to bridge once, and usually twice, the smaller streams of Georgia, it could not span the Tennessee by nearly half. We put Hood across at Florence as he advanced into Tennessee by supplementing it with a trestle bridge. After his disastrous defeat at Nashville, we put him over Duck River at Columbia. There the condition of the roads and our teams compelled us to abandon the chords and decking of the bridge. We were there informed that the general had selected Bainbridge as the point at which he would attempt to recross the Tennessee, and we were ordered to hasten forward with the battalion. At the same time Capt. Cobb was dispatched with his company of pontooniers, mounted on mules, to Decatur to bring down if possible several pontoon boats that had been captured there. The whole corps of engineers felt that upon his success depended the fate of the army, and we all knew that to run the muscle shoals at that stage of water, in such frail boats, was a most hazardous task. So much so that we could not allow ourselves to calculate upon his success.

As we approached the river late on the second afternoon with that grand old army, disheartened,

disorganized, wrecked, behind us, and the broad Tennessee river before, while the roar of artillery in the distance told too plainly that the rear guard was being pressed by the victorious foe, the gravity of the situation was oppressive — the river too deep at that stage to admit of a trestle bridge being built quickly and boats enough to span but half the stream.

Just then the chief engineer, riding rapidly, came up, his face all aglow, his fine gray eyes sparkling, and exclaimed “Cobb has come.” “Cobb has come”, was passed down the line, and a wild cheer for Cobb went up from the old battalion, for all felt that the army was saved. That cheer was taken up, echoed and re-echoed by wooded hills and riverbanks.

May the angels that guard the other shore of the silent river he has crossed catch up the echo and pass the exclamation, “Cobb has come,” on up the line to the throne of heaven,

N. PHARR.

Without those pontoon boats, that Christmas Day in 1864, there would be no bridge and Hood’s army would most likely have been forced to surrender there a few days later. The area between Shoal Creek & Indian Springs, west of Florence, may have ended up as another large National Military Park. But, 24-year-old Cobb had saved the day for the Army of Tennessee.

So if you venture out on Wilson Lake, just downstream of Shoal Creek, over the old Muscle Shoals, perhaps on a bitter cold, frosty, Christmas afternoon, don’t be surprised if you hear some faint “Rebel yells” along with a shout, “Cobb has come! Cobb has come!”