By Greg Gresham

North Alabama Civil War Round Table

MSNHA note: This post includes contemporary Civil War accounts using language we consider offensive today.

We have many Civil War stories about the challenges of crossing the swift Tennessee River in the Shoals area–stories that remind us of once strong & powerful shoals.

In one instance, a Confederate cavalryman remembered his escape during the end of Wheeler’s September, 1864, raid. (This crossing was at the Colbert Shoals)

“We got to the river about midnight and marched across. I swam 4 times. Some of the boys went too low and could not get back. They cried very piteously for help. I was got out but the Lord only knows what became of the others………It was dark as I came over. The moon had gone down and it was very dark, the water was swift and deep as my mule swam past the shoal. The poor fellows that had been swept over by the current and could not get back uttered the most piteous cries for help. Others were praying. I thought, taking everything else under consideration, that it was the most solemn moment I ever saw.”

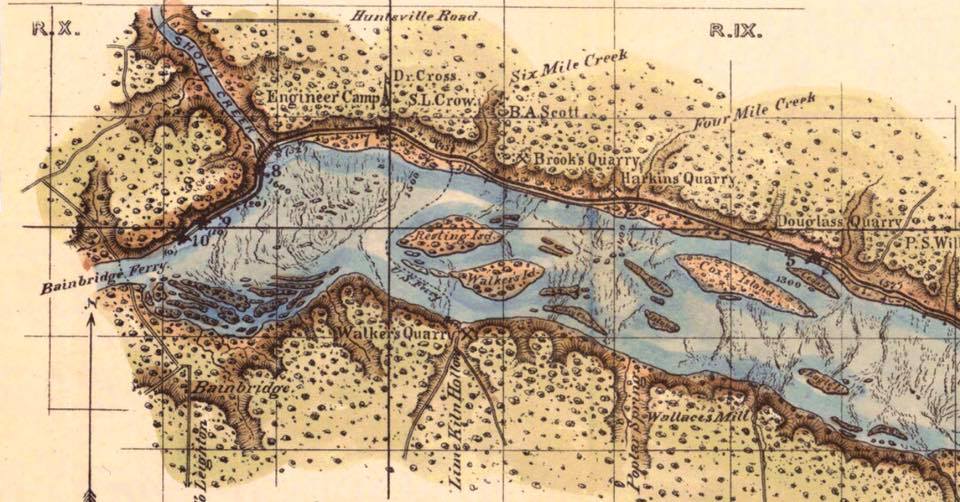

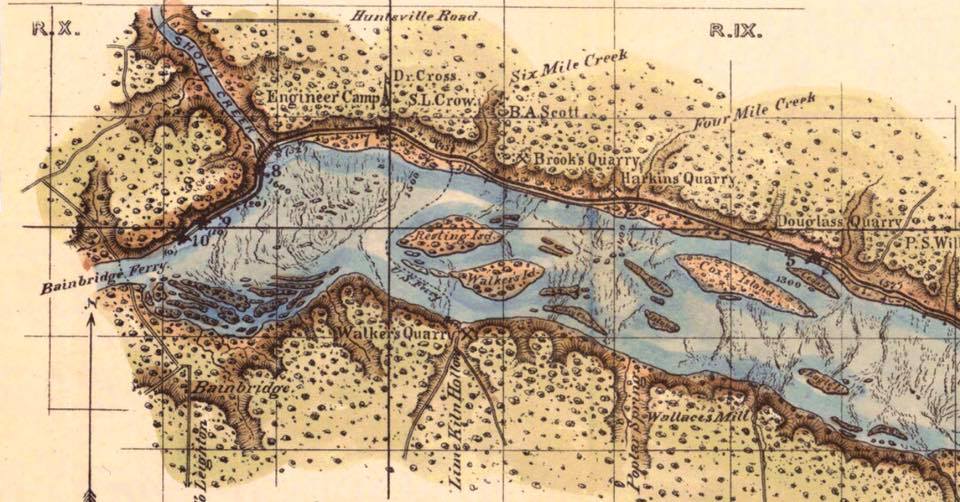

Another Rebel trooper spoke of being shot at it while crossing the shoals near the Bainbridge Ferry in April, 1864, during one of Roddy’s pushes across the river that spring:

“About sundown, our Captain ordered us to mount our horses very quietly, and detailing a rear guard of ten men to hold the ford led the rest of the company in column of twos into the water toward MacKernan’s Island. We were going to try to ford or swim to it, provided we were not shot in the attempt. The stream in some places was only a foot or two deep, then without warning we would plunge into a hole, which would swim our horses, and the next moment have to climb up steep rocks, into another shallow place. It was very slow work crossing with such a rough bottom, but still we made some progress forward, and gradually after going 300 yards, we got from behind the trees which had sheltered us this far from the view of the Yankees, and then the trouble commenced. ”Bang” went a carbine and a bullet struck the water near us. Soon came another and then half a dozen. We could not fire in return, and we were going forward more slowly than a funeral procession; I crouched down on my horse’s back and made myself as small as possible, but thought every moment that I would get a ball through my back. It is one thing to charge shooting and yelling, and full of enthusiasm; but another kind of courage is needed, when you feel you are being potted like a turkey, by a lot of men who are not in any fear of being fired at in return. Another volley came, one bullet struck the man beside me in the calf of his leg, and spattered the water in my face, he yelled loudly but clung to his horse; had he fallen off, he would surely have drowned.”

Many old butternuts talked of the shaky pontoon bridge’s struggle to remain intact during December, 1864, at the Bainbridge Crossing. Here are a few of the more descriptive ones:

“At last the Tennessee River was reached. There was a pontoon bridge, a frail looking affair, as if it were nothing but inch boards laid on top of the water, the current being so strong that it was in the shape of a rainbow; yet all the command passed over safely, the cavalry being the last to cross.”

“When we got back to the Tenn. River our time came to cross the pontoon bridge about midnight, and it was very dark. Gen. Cheatham was there to see that every thing started on the bridge in proper order. Orders were to dismount and lead across, but there was no walking for me, so I kept my seat and was on the bridge when Gen. Cheatham hailed out, ‘Why in the ____ don’t you dismount?’ ‘I have a sprained ankle. General, and can’t walk.’ ‘All right, if you are a mind to risk it I will.’ When a boy I rode bucking mules, jumping horses, young steers and a railroad train with wheels jumping the but all this was pleasure compared with that pontoon ride. The river was bank full, the bridge in a swing, jumping up and down. My eyes being up above the rest, the lights on the bank in front blinded me like a bat. It seemed to be the widest river in the world.

“We passed on through the mud and slush until we finally came in sight of the Tennessee River, with its wide expanse of murky waters bearing down the stream drifts of logs, trees, brush, and everything imaginable. We could see, too, a rickety pontoon bridge hastily and insecurely built. It was serpentine in shape, about twelve feet wide and half a mile long, covered from end to end with all kinds of beasts, wagons, and, in fact, you could see everything in the shape of humanity except women and dogs. Besides this, there was a Yankee gunboat half a mile or more down the river throwing bombshells, trying to break the bridge ; but the shoals prevented it from getting near enough to do any damage. The north end of the bridge had a promiscuous mass of humanity and animals all trying to get on and over the bridge at the same time. Finally my time came, and I went forward in great fear that the cable would break and let us all go down into eternity together. But the Lord was surely with us and permitted us to reach the southern shore without the loss of one. I turned my eyes toward the northern bank, and O what a sight ! Just then I agreed for myself and all concerned that I would no more cross that river in the interest of secession.”

But, perhaps, the most interesting account of an escape across the shoals came from 20-year-old Union POW Peter D. Whitzel. Pvt. Whitzel & his companion, 24-year-old Sgt. William H.H. Baker of the 61st Illinois Infantry, made their dash back to Union lines as the last of Hood’s Army crossed the Tennessee on retreat southward. By moving east & away from Hood’s army, they avoided most of the patrolling Confederate cavalry protecting his rear. But they faced a daunting challenge in crossing the roughest part of the Muscle Shoals. Here’s the story:

“Among the few prisoners that Hood’s shattered army carried South with it after its overthrow at Nashville were the 61st Illinois, the greater portion of whom had been captured by Gen. Bate a few days before in a small battle near Murfreesboro. I was one of the captured, but perceiving that the confusion of the rebels made escape easy, I was at no time in fear of a rebel prison. Twelve days elapsed, however, before I effected an escape.

We crossed the Tennessee River on the morning of Dec. 27th, 1864. Upon the farther side a wagon train, halted in the road, threw the guards and the prisoners together in considerable disorder. My comrade, Baker, and I profiting by the confusion, stepped from the ranks, crossed a little ditch and disappeared in the forest.

The beginning of our escape was thus comparatively easy, but the task that remained of evading the guerrillas and recrossing the river was one of great danger. The high water in this instance largely increased the natural difficulties of our flight. The river was spread over miles of the low lands roundabout, and we were often compelled to wade waist deep in icy water.

About noon a negro informed us where a small boat lay hidden, but he advised us not to try to cross the river, as the Muscle Shoals during this high water were extremely dangerous, and, besides, every island therein was filled with guerrillas.

But Baker was an old river man, and neither of us feared the guerrillas as much as we did Andersonville. Therefore, we determined to push across, if possible. We found the boat without trouble, but were surprised at seeing nothing more serviceable than a hollowed-out log, usually called a dug-out. In this crazy craft we were reckless enough to attempt the dangerous crossing.

It was almost a quarter of a mile through more or less heavy timber from the edge of the deep water to the open current, and beyond the current lay what looked like the farther bank, but what we surmised might be an island. The passage thither was by no means free from danger. Through every space between the trees, and through the straits which divided the numerous little points of land that broke the surface, swept the tumbling waters, and it was only by a most determined struggle that we approached our goal.

Catching to the trees along the lower end of a small island, we would pull the boat laboriously up stream; then we would make all ready, and shoot out across the furious current toward the next resting place. Thus, step by step, we lessened the distance between our boat and the open stream. We had not yet emerged from the belt of timber when we saw a raft detach itself from the land and swim slowly toward us. As it came nearer, we discerned upon it two long sweeps, a stack of guns, and 12 or 15 men. The men were guerrillas, of this there could not be the slightest doubt. Therefore, we pulled the dugout alongside one of the smaller islands, and concealed ourselves as well as possible in the overhanging shrubbery. The raft entered the timber not a hundred yards below us and walked, as it were, directly past us toward the bank. Death for once saw not his victim. As soon as his grim ministers were out of sight, we shoved out from the timber and fought our way into the current. It was now about 3 o’clock, and our hunger, somewhat active even when we escaped, had increased alarmingly. We were ready to risk almost everything for a meal, and we decided to obtain one at the first house on the land we were approaching. There seemed the less danger in this because we might naturally suppose all the men in the vicinity had, gone away.

But as it was unnecessary to hazard two lives, it was decided that I should make the attempt alone, with the understanding that if I was too long absent, Baker should believe that I had been captured, and should act then according to his own judgment As soon, then, as the boat, hurled by the current, plunged against the bank, I sprang out and walked toward a little cabin that stood on the highest point of the land. The door was open, and I glanced inside. Two or three boxes of cartridges were piled in one corner, a number of muskets were leaning against the wall, and the muzzles of a hundred more were protruding from the loft. The whole place had the appearance of an arsenal. It might have been foolish to come, I thought, and it will be the purest chance if I ever get away, but I can’t back out now. Without stopping to knock, I passed inside, marched across the floor and halted before the fireplace. Two women, one of them black, stared at me in surprise as I entered. Their eyes rested particularly upon my clothes, which, although some what modified by exchanges with the rebels, still bore a close resemblance to a Yankee uniform.

‘Can you tell me where Courtland is?’ said I, mentioning a town on the northern shore.

‘About three miles from heah,’ replied the white woman, ‘a’nd on t’other side of the river. How’d you get over to this island?’

Then this was an island, as Baker and I had guessed.

‘On a little raft,’ I answered. ‘Do you think we can go on across with it?’

‘No, you can’t. You’ve got half a mile of open watah to cross, and the rapids are powerful bad this yeah. A few days ago, ouah men tried to take some women across on a little raft, but the raft upset and the women were drowned.’

‘Do you mean those men that went over to the other shore a few minutes ago?’

‘Yes.’

‘What are they Confederates or Yanks?’

‘Oh, Confe’rates, of course. My man is there, and he belongs to Joe Shelby’s cavalry. Who be you?’

‘I belong to the 12th Ark., and have just got away from the Yankees. I want to go to Courtland. Do you reckon I could get your men to put me across the rapids?’

‘If you’re not a yank there won’t be no trouble. But them blue clothes will make you do a heap of explaining.’

‘Why, dem ar men’d kill you jis like a worm!’ broke in the old negress. ‘Course’n yer ouah man,’ she added. ‘It’s different, but … “

‘I’m all right, auntie,’ said I, coolly throwing back my overcoat and showing a rebel jacket. ‘When will the men be back?’

‘Mebbe in an hour, mebbe not till dark. They’re out looking for Yanks.’

‘Well, I might as well wait till they come back. And, er, have you got anything to eat about the place?’

The negress at once placed an oyster can of milk and a big corn-pone on the table and invited me to be seated. The women seemed so friendly that I ventured to inform them of there being two of us and to bargain with them for a regular dinner. The old negro woman hastened to set about the cooking, and I, having finished my bread and milk, went to summon Baker.

Baker was already very uneasy; but my coming reassured him. As quickly as possible I reported my success and described the character of the inn at which we were stopping. Then, launching the dugout, we paddled carefully around to the northern side of the island and fixed everything in readiness to push out into the river at a moment’s notice. When all was arranged to our satisfaction, we went together to the cabin.

Our dinner consisted of bacon, gravy, cornbread and milk, the typical Southern meal; but we were used to such fare and ate heartily. While we were eating, the old negro woman grew very anxious. She walked nervously back and forth begging us to hurry, and declaring that the ‘men folks ‘ll kill ye suah if they cotch ye.’

I soon finished my dinner, for the earlier lunch had partly satisfied me, and gave the woman a $5 Confederate bill in payment for our meal. She remarked that she would prefer a greenback for $1 if I could give it to her. I had the greenback, but I, too, preferred it to the rebel money; so I pressed the larger bill upon her. I was beginning to get very uneasy myself. We had remained upon the island almost an hour, and the guerrillas were likely to return at any moment. But Baker ate calmly and deliberately it seemed to me he would never finish. Two or three times he noticed my impatience and remarked that he was going to eat enough while he had a good chance, danger or no danger.

I kept walking from the window to the door and from the door back to the window, watching closely for the guerrilla raft At length I stepped outside of the door and surveyed the river in a new direction. There was the raft, already close to the island, and approaching with great rapidity. I stepped back and nodded to Baker in a manner that could not be misunderstood. He took not another mouthful. Rising in haste, he thanked the women for their hospitality, and followed me out of the house. When we had turned the cabin corner we sprang into a run, and at the same time began, taking off our outer clothing. It might prove fatal to us to been cumbered by clothes in case the dug-out, a very unstable craft, indeed, should capsize. In a few moments we reached the water, then pitching the clothes into the dug-out and springing in ourselves, we pushed off from the dangerous island into the scarcely less dangerous river.

‘Now,’ said Baker for while I had been taking the lead upon land, he was master upon water, ‘now, boy, don’t you pay any attention to how the boat goes. Pick up that can and bail all the time, but keep yourself as steady as possible. And if the boat tips over, you. climb right on top of it. Don’t let anything get you away from this log; stick to it always. Tip Baker will get you over. And when we reach the other side don’t go to grabbing at the trees; wait till we land. Now, you pay attention to what I have said.’

I obediently reached for the can, and just as the guerrillas arrived at their cabin, Baker with a few quick strokes sent the dug-out directly into the main current. Instantly we were snatched round and round and whirled down stream at least a hundred yards; but with his oar Baker fought like a demon, and, at length brought the boat under control. The waves of the rapids dashed over the sides of the craft, half filled it with water, and threatened every moment to overturn us. I worked with my can as if my life depended upon it, and with all my exertions barely managed to keep us from swamping.

But Baker was all right. He headed the boat this way and that, to avoid the dangerous waves — now shooting swiftly through a small one, now holding back desperately that a large one might pass by, now pulling violently sidewise to shun a frowning rock, or riding with breathless rapidity down the foaming current. And ever as we darted along, the roar of a fall below us grew and increased, until it almost overtopped the clamor of the rapids. But all the time the northern shore became more and more distinct, and the volume of water slipped farther and farther southward. At length we passed out of the surging channel into the quieter waters near the side. The difficulty now was in landing, for the banks were almost perpendicular, and the overhanging trees threatened to pull us out of our boat. I was wrought up to such a pitch that as soon as we drew near I began catching at the branches. The boat dipped, whirled round, and shot back into the current. Baker swore viciously, and with the greatest difficulty coaxed the boat back to the shore. This time we succeeded in making a landing, and we climbed the bank not a stone’s throw above the cataract.

The guerrillas attempted no pursuit, for they doubtless supposed we would drown. Our peril indeed had been great, and only an experienced boatman, aided by good fortune, could have brought us through. But now we were saved, both from the deadly rapids and the heartless guerrillas. Upon the very next day we re-entered the Union lines.”

Peter and William survived the war. Peter died at 57, in Kansas, in 1901. William, however, died at age 35 in 1875 of consumption, as so many others during that time, and is buried in Oklahoma.

The Muscle Shoals, born long before either of them, would not last much longer into the 20th century. Wilson Dam took out most of the Muscle Shoals in the 1920s. Pickwick and Wheeler Dams took out the rest a few years later during the TVA expansion. While the taming of the shoals brought much needed progress and cheap energy, one wonders if the shoals themselves could one day escape the dams that contain them.

Blog-post author Greg Gresham is doing stuff he likes to do after retiring from 33 years in the pulp & paper industry. When he’s not golfing or enjoying being a grandfather, he digs into historical research with an emphasis on Civil War era local history. Sometimes he stumbles on intriguing yarns from years ago, or–with a little luck–he solves a mystery or two. Those, he says, make good stories.

“About sundown, our Captain ordered us to mount our horses very quietly, and detailing a rear guard of ten men to hold the ford led the rest of the company in column of twos into the water toward MacKernan’s Island. We were going to try to ford or swim to it, provided we were not shot in the attempt. The stream in some places was only a foot or two deep, then without warning we would plunge into a hole, which would swim our horses, and the next moment have to climb up steep rocks, into another shallow place. It was very slow work crossing with such a rough bottom, but still we made some progress forward, and gradually after going 300 yards, we got from behind the trees which had sheltered us this far from the view of the Yankees, and then the trouble commenced. ”Bang” went a carbine and a bullet struck the water near us. Soon came another and then half a dozen. We could not fire in return, and we were going forward more slowly than a funeral procession; I crouched down on my horse’s back and made myself as small as possible, but thought every moment that I would get a ball through my back. It is one thing to charge shooting and yelling, and full of enthusiasm; but another kind of courage is needed, when you feel you are being potted like a turkey, by a lot of men who are not in any fear of being fired at in return. Another volley came, one bullet struck the man beside me in the calf of his leg, and spattered the water in my face, he yelled loudly but clung to his horse; had he fallen off, he would surely have drowned.”

“About sundown, our Captain ordered us to mount our horses very quietly, and detailing a rear guard of ten men to hold the ford led the rest of the company in column of twos into the water toward MacKernan’s Island. We were going to try to ford or swim to it, provided we were not shot in the attempt. The stream in some places was only a foot or two deep, then without warning we would plunge into a hole, which would swim our horses, and the next moment have to climb up steep rocks, into another shallow place. It was very slow work crossing with such a rough bottom, but still we made some progress forward, and gradually after going 300 yards, we got from behind the trees which had sheltered us this far from the view of the Yankees, and then the trouble commenced. ”Bang” went a carbine and a bullet struck the water near us. Soon came another and then half a dozen. We could not fire in return, and we were going forward more slowly than a funeral procession; I crouched down on my horse’s back and made myself as small as possible, but thought every moment that I would get a ball through my back. It is one thing to charge shooting and yelling, and full of enthusiasm; but another kind of courage is needed, when you feel you are being potted like a turkey, by a lot of men who are not in any fear of being fired at in return. Another volley came, one bullet struck the man beside me in the calf of his leg, and spattered the water in my face, he yelled loudly but clung to his horse; had he fallen off, he would surely have drowned.”