By Jordan Collier

Assistant Genealogy and Local History Librarian

Florence-Lauderdale Public Library

It may come as a surprise that industry in antebellum Lauderdale County was remarkably advanced and diversified.

Abundant streams such as Cypress Creek, Shoal Creek & Bluewater enabled the development of water-powered mills of a variety of sizes and purposes. Virtually every stream was host to sawmills, grist mills or textile mills. Famous examples of antebellum factories in Lauderdale County are the Kennedy gun factory near Green Hill, Globe Cotton Mill on Cypress Creek & the Baugh, Kennedy & Co. factory on Shoal Creek — also known as Lauderdale Factory.

According to research published by Richard Sheridan in the Journal of Muscle Shoals History, the Baugh, Kennedy & Company factory opened in 1845 and operated 34 looms with power supplied by a dam 10 feet high and over 400 feet long. At the site of the factory was a village containing a school, church & cottages for the workers. In addition to 66 paid workers, a number of enslaved people also labored at the factory. One of these was Henry Dunn, a blacksmith whose labor was hired out to the factory by his so-called owner, John Wilson. Dunn was permitted to do extra work for himself in his off time. Through his hard work & industry, he managed to accumulate property of his own.

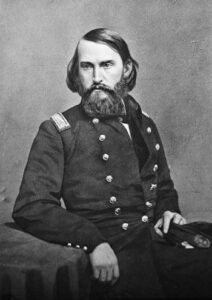

As I first began researching the Civil War in the Shoals and analyzing the documents preserved by the Southern Claims Commission, it became evident that the Lauderdale Factory was a place of remarkable importance in the community in its day. The factory’s ledger books have been preserved through the University of Alabama’s Special Collection. They bear witness to a diverse & thriving business. In March 1862 when floodwaters damaged bridges and factories in Lauderdale County, the Florence Gazette reported that “Two hundred and fifteen or twenty bales of cotton, belonging to Baugh, Kennedy, & Co., were swept away from their Factory on Shoal Creek, part of which, probably, has gone to the yankees, as it was seen passing this place floating In the river. Some of the bales were caught.” Gen. Grenville Dodge’s forces occupied the factory on their march from Corinth to Pulaski in November, 1863. Gen. John Croxton also occupied it as he skirmished with Confederates under Gen. John Bell Hood along Shoal Creek in November, 1864.

Despite its apparent prominence in the community, no trace of the factory is visible today. Pinpointing its location would seem to be simple at first glance. Contemporary sources are clear: the factory was located on Shoal Creek where the Nashville Road crossed the creek. The Southern Claims petition of Henry Dunn even pinpoints its location to the nearest mile: 9 miles north of Florence on the Nashville Road. (“Nashville Road” almost certainly refers to what we know as Jackson’s Military Road, largely coterminous with Lauderdale County Road 47, which crosses Shoal Creek in the community now known as Happy Hollow). Given these two sets of criteria, i.e that the factory was both on Shoal Creek and on the Nashville Road, a precise coordinate is easily established.

And yet, the precision of this coordinate belies the complexity of another piece in the puzzle: where did the Nashville Road cross Shoal Creek? It is tempting to merely conclude that it crosses today where it crossed in the 19th century. Some roads definitely do follow the same path they took originally. The city of Florence, for example, which was surveyed in 1819, clearly follows the same pattern today as was laid out then, with some notable exceptions which are easy to determine by comparing maps. Rural locations, however, can be trickier to pinpoint.

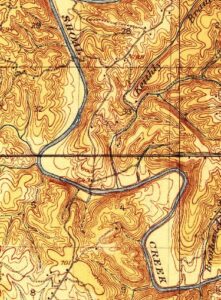

The earliest extant maps of Lauderdale County are often more figurative than literal in their depictions of physical features. They show the general course of a road, for example, but may not be a 1:1 representation of where that road precisely was in the real world. By the turn of the 20th century, improvements in surveying & printing produced maps that showed real world features with a high degree of accuracy. One such map, a 1916 topographical map produced by the U.S. Geological Survey, shows a route of the military road that is virtually identical to the present-day route — except at the Shoal Creek crossing.

The route it shows follows modern CR 317 where it bows off from CR 47 to the north and continues along the contour of the terrain down to the water’s edge. According to the late historian William Lindsey McDonald, the road then crossed Shoal Creek with a bridge that was constructed in 1829. The stone pillars of this bridge are still clearly visible on satellite imagery. It was replaced in 1927 by the current crossing approximately three-quarters of a mile downstream, when the entire route was changed.

Having verified the location of the original crossing, one question remains: which side of the creek was the factory on — the north or south? I haven’t found a contemporary 19th-century source that specifies. However, research submitted to the Alabama Historic Commission in 1996 to designate the military road as an historical site said that Baugh Kennedy & Co. “… is located along Jackson’s Military Road on the southern shore of Shoal Creek.” The source cited an article in the Journal of Muscle Shoals history by Richard Sheridan titled “Industrial Growth in the Shoals 1818-1933,” which (despite providing extensive detail) itself does not locate the factory on the south shore.

Personally, I find a south shore location

surprising because the terrain is steep up to the shoreline with only a small level swath surrounding the crossing. The north bank has a wide open plain in the bend of the creek, which seems to be a natural location for development. There is also this from Croxton, dated Oct. 31, 1864: “I hold Shoal Creek, seven miles east of Florence, and Bough’s [sic] Factory, nine miles north. The enemy have crossed a large force, but have not yet struck out for their destination.” The Confederates at this moment had just crossed the Tennessee River & occupied Florence. It would be the natural strategic choice for Croxton to place the creek between himself & the Confederates to hold as a line of defense. That would mean locating on the north & east banks. If he held Baugh’s Factory, as he states, it follows that the factory was on the north shore. But this is only an inference — Croxton did not specify.

If we take the researchers at their word, with a cautious grain of salt, it seems the factory was tucked in the narrow stretch of level land on the creek’s south bank. Sheridan’s article doesn’t say which side of the road the factory was on, and I can’t hope for specificity unless archaeological surveys were conducted on the site. Then again, historical questions are rarely answerable without a healthy dose of uncertainty. And the pursuit of answers to such questions wouldn’t be nearly as fulfilling if they were all so easily answered.

3 Responses

Have you asked Richard if he has any more information? I have his contact information if you need it.

Thanks, Mary! I’m not sure if we have but mail that info to msnha@una.edu & we’ll pass it on. Much appreciated.

I have a period map that confirms it was on the south side.