By Lee Freeman

Florence-Lauderdale Public Library Local History-Genealogy Dept.

Florence native Lee Freeman has been the local historian-genealogist at the Florence-Lauderdale Public Library since 1997. The author of one book & several articles, he serves on many local history & historical preservation boards. He has been happy to serve as an MSNHA sometime-consultant.

Many people are surprised to learn that historically, until legalized segregation began pushing them out in the 1920s and 30s the heart of Florence’s black business and professional community was located downtown, not in West Florence. What surprises people even more is the large number of African-American businesses in downtown Florence between 1818 and 1930—approximately fifty-two that we know of.

By 1820 there were 3,556 whites, 1,378 slaves, and 29 free people of color (blacks who weren’t slaves) in Lauderdale County (like many states, Alabama had laws on the books prohibiting free black residence however in Lauderdale, as in many other places, these laws weren’t enforced as long as free blacks filed their free papers at the court house).

One of those free people of color and the earliest recorded black Florence businessman was mulatto John H. Rapier, Sr., a Nashville slave hired out by his Thomas owners to Florence merchant Richard Rapier and freed in 1829, after Rapier’s death. John’s son James Thomas Rapier was elected to the US House of Representatives on the Republican ticket in 1872 (until FDR’s New Deal of the 1930s most blacks voted Republican as it was the party of Lincoln and emancipation). Local mulatto and former freedman Rush Patton, Sr. opened a livery stable in late 1865 and was soon awarded a US mail contract.

Florence boasted black merchants/professionals from a variety of trades: there were several cobblers such as George W. Seawright; several barbers such as Constantine T. “Constant” Perkins, Sr.; carpenters and housepainters; chiropodists and hairdressers such as Bessie Foster; theater owners/managers like Bessie Foster; grocers like WH Dismukes and Jacob Wytch; blacksmiths such as Hilton Key; bricklayers; cooks/restauranteurs such as Abe Streiter; bootblacks; musicians; hackmen (a hack was a carriage used as a taxi); liverymen such as Jesse Patton; morticians such as Henry MO Terry; and at least one amateur architect, barber Constant Perkins, Jr., who designed the new sanctuary of St. Paul AME Church on the NW corner of Court and Alabama Streets in 1895.

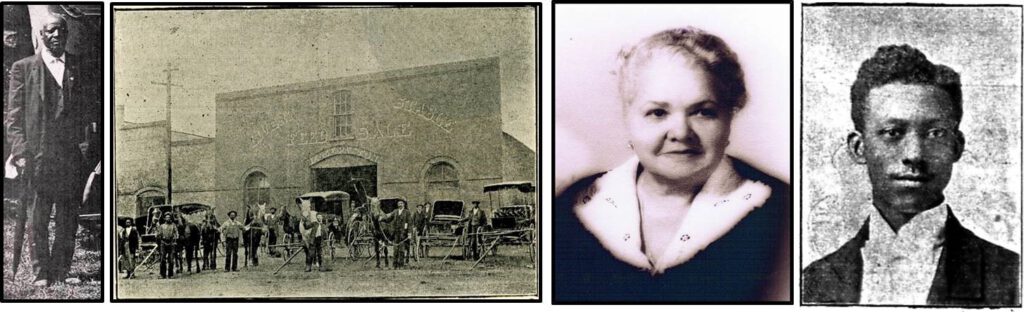

Above: From left, former slave, Civil War veteran (a body-servant to his master), and Florence cobbler George W. Seawright (1848-1931), at the annual 1921 United Confederate Veterans’ reunion at Mars Hill, in Lauderdale County; Jesse Patton’s (1865-1910) livery stable on W Tenn. Street near Court Square from Patton’s Dec., 1900 Florence Herald biographical sketch (Patton is front row right holding reins); Bessie M. Foster (1887-1963), Florence’s earliest known black female businesswoman; “Boss [bicycle] repairman” Percy H. Casey (1872-1902) from his 1897 Florence Herald biographical sketch.

During the 1890s the Stafford Block of East Mobile and Court Streets was home to a cluster of black-owned business—George Seawright’s cobbler shop in the 1890s; Abe Streiter’s Negro restaurant in 1891; William H. Dismuke’s grocery store next door to Seawright’s shop in 1897; and Jake Wytch’s grocery in the Court St. area of the block in 1898. Other locations of black businesses included Ben Thomas’s Negro restaurant on the corner of Tennessee and Seminary in 1905; Hilton Key’s blacksmith shop on Tombigbee near Court (the site of the modern Tombigbee Court Apartments); and 314 East Limestone Street, the first location of Henry MO Terry’s funeral home in 1913-1914. Bessie Foster opened her Pastime Theater for Negroes on “Sweetwater [Street] near Court,” in 1916 while her hair salon/chiropodist business was located on Tennessee Street upstairs over the Chamber of Commerce office in 1917 and upstairs at 109 S Court in 1925. Dr. JA Simpson’s home and medical office were located at 417 S Court in 1935, while Dr. Emory Jones’ dental practice was on the corner of Court and College in 1912.

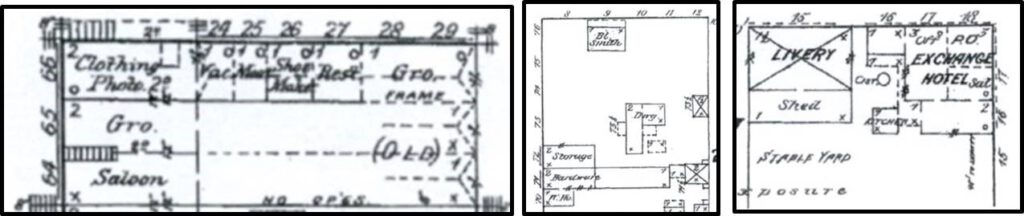

Above: L, the Stafford Block of East Mobile Street from the Sanborn Fire Ins. Maps of 1889, showing George W. Seawright’s cobbler shop (no. 26) and Abe Streiter’s (1940-1893) restaurant (no. 27.) This block of buildings burned in Dec. of 1891 and was rebuilt as the Perry Block in 1893. Seawright’s shoe shop was there as well as Jacob Wytch’s (1848-1927) grocery in 1897 (fronting Court St.) as were Albert Pierson’s barbershop and William Poe’s restaurant in 1914; M, Hilton Key’s (1832-1895) blacksmith shop (at top) on “Tombeckbee near Court” in 1884; R, Rush Patton, Sr’s (1837-1907) livery stable on W College in 1884.

These black Florence businesses routinely advertised in white newspapers as well as Polk’s City Directories, and apparently catered to both black and white customers. A few like Jesse Patton and “boss [bicycle] mechanic” Percy Casey had biographical sketches published in the white papers.

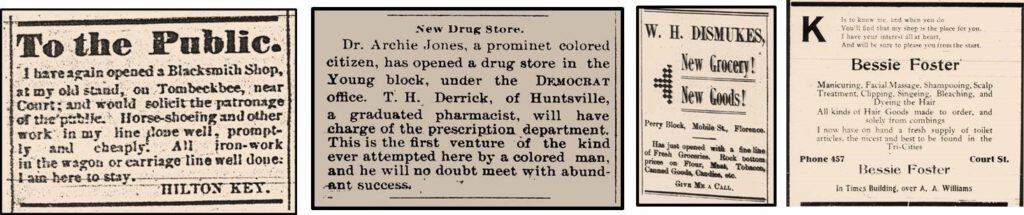

Above, newspaper ads for Hilton Key’s (1832-1896) blacksmith shop from the Florence Gazette, Sat., June 12, 1886; April 20, 1900 Florence Democrat article on the opening of Dr. Archie Jones’ drug store; Ad for WH Dismuke’s (ca. 1875-aft. 1901) grocery store from the Florence Herald, Thurs., Sept. 21, 1899; ad for Bessie Foster’s Hair-dressing parlor, part of a larger ad for a Florence Merchant’s Contest she participated in from the Florence Times of Fri., March 8, 1912.

Florence’s short-lived black newspaper was The Watcher, published by AME Church pastor Rev. JW Williams of Centre Star. The paper published from 1888 to 1889 and Rev. Charles Bernard Handy, WC Handy’s father, was its assistant editor, later its business manager.

Yet even more impressive than the number of black businessmen in Florence was the number of doctors, eleven that we know of between 1893 and the 1930s—five physicians, three dentists, and three pharmacists: Florence native Dr. Thomas Murdock, MD, who practiced in Chicago but died in Florence in 1893; druggist Dr. Henry Clark, whose store in 1926 was on S Wood Ave.; druggist Dr. Archie Jones, a Madison County native and Meharry graduate whose shop opened in 1900 over the Florence Democrat office; pharmacist Thomas H. Derrick; Dr. George Washington Coffee, MD (who practiced in Florence for nine months in 1906); Dr. Charles Gray, MD; Dr. Emory Jones, DDS; Dr. JE Jones, DDS; Dr. LM Pollard, DDS; Dr. James A. Simpson, MD. Arriving relatively late, in the 1930s, Dr. Leonard Jerry Hicks, MD became the namesake of the modern Dr. Hicks Boulevard.

In December of 1867 five black police officers were hired in Florence, one for daytime duty four for night patrol. At some point prior to 1870 this system was discontinued; by September of 1921, when black resident Will Vaughan was hired by the Florence Police Dept. to patrol the black business district of East Florence there were no other blacks on the force. Unfortunately, Vaughan had no authority over whites and received no salary, instead being paid from fines levied on offenders. ###