By Greg Gresham

North Alabama Civil War Round Table

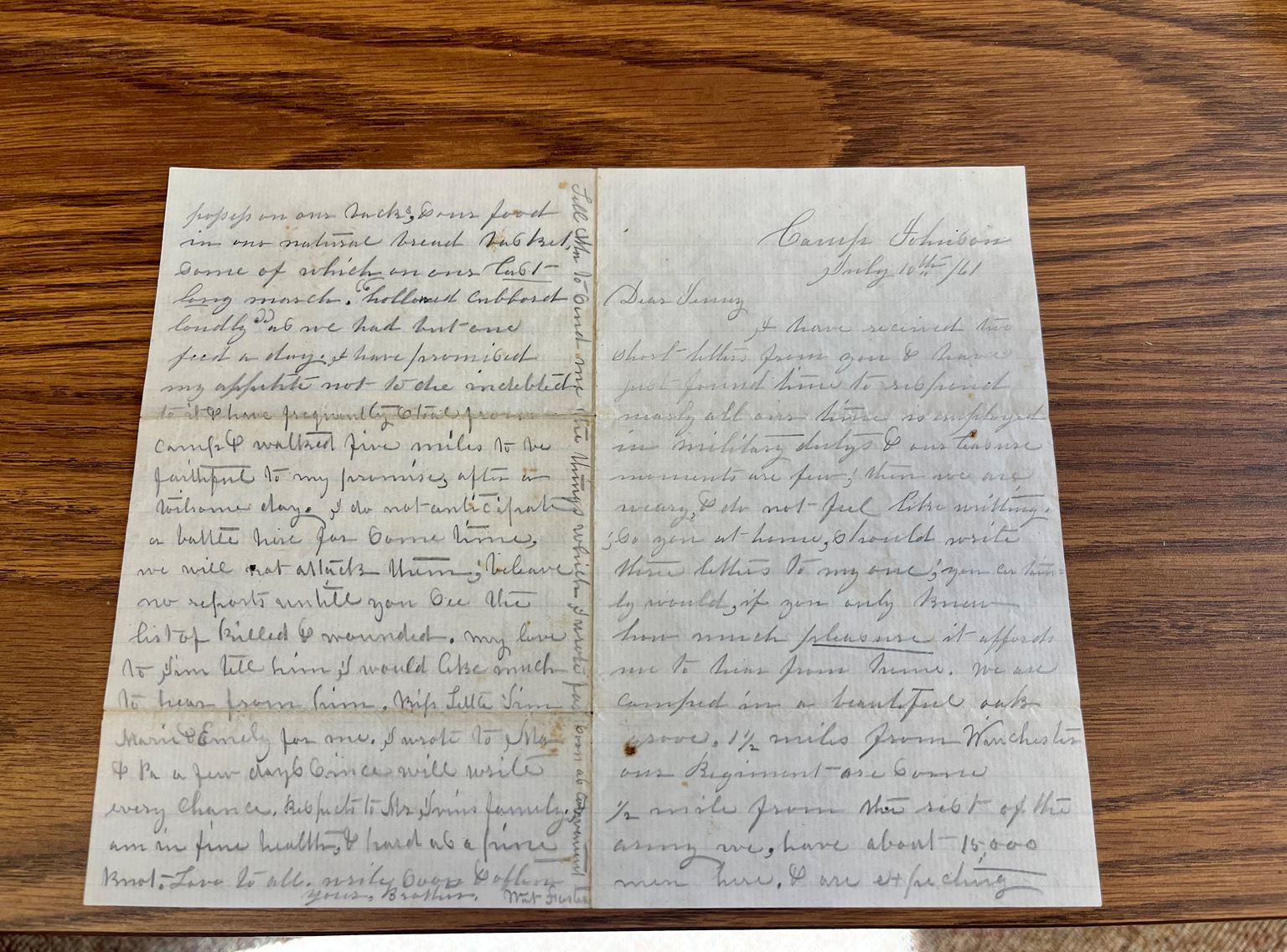

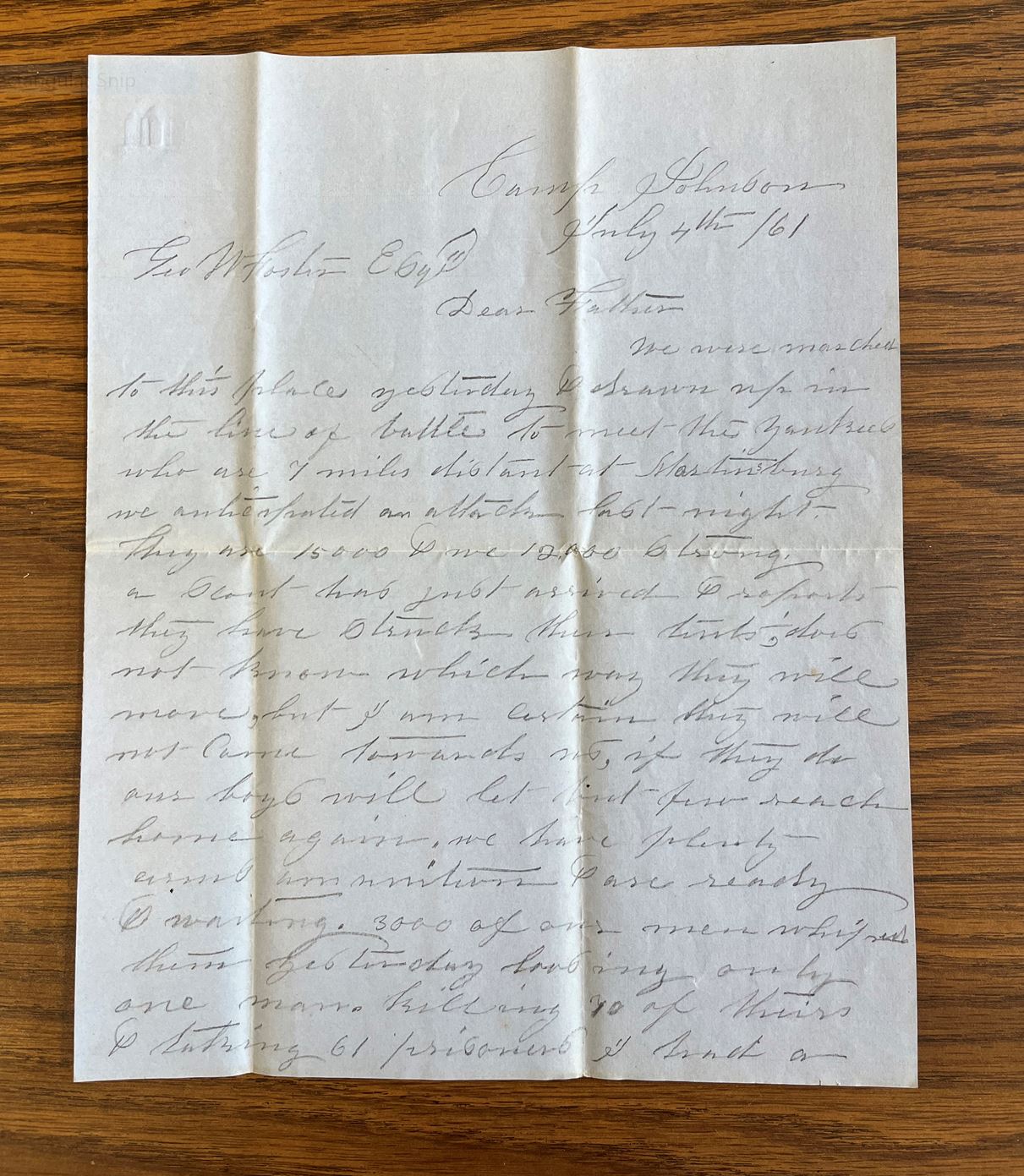

Often, while researching period documents of the Civil War, one finds names of towns, creeks, landmarks, etc. that don’t match their current names. Roads used during that time become abandoned, perhaps forgotten, and trying to retrace old events becomes difficult and sometimes impossible.

Union Gen. George H. Thomas had placed Federal cavalry to watch Hood’s movements. At first he had only Gen. John Croxton’s reinforced brigade, which was roughed up quite a bit when Hood first crossed the river & then several days later at the Huntsville Road crossing of Shoals Creek. Thomas, as quickly as he could get more cavaliers diverted to his department, added Gen. Edward Hatch’s full cavalry division to Croxton’s command. That gave Hatch over 3,000 mounted troops & several pieces of artillery to watch Hood from the east side of Shoals Creek. Coon’s brigade was part of Hatch’s division. There was also as small Union cavalry brigade stationed around Waynesboro but there was no link between the two commands, leaving a hole in the Union lines that Thomas increasingly worried the Rebels would exploit.

“November 16, left the military road at 8 a. m., passed down the valley of Wolf Creek, and crossed Shoal Creek at Wolf Ford (this is just north of the Alabama-Tennessee state line); moved from the opposite side to Aberdeen (near present-day Pruitton), thence to Big Butler (creek), and down to Little Butler (creek), from which place moved directly south toward Wilson’s Cross-Roads (present-day St. Florian). After passing a mile, the advance, the Second Iowa Cavalry, found the enemy’s pickets (most likely posted at the crossroads of county roads 8 & 61) and dashed at them furiously, and ran them into their reserve pell-mell, which created a stampede of the whole command, composed of General Roddey’s brigade, which, in turn, ran back to their infantry camps in great confusion. Through the gallant conduct of Lieutenant Griffith, of Company D of the above named regiment, we captured several prisoners, who informed us of many important facts touching the movements of the enemy. After having forced Roddey within the infantry lines, I became satisfied that the enemy were continually receiving re enforcements, and that Forrest had recently joined Hood (on the 14th), and that the location about the two Butler Creeks was not the most safe for the camp of a cavalry command. I therefore took the responsibility of recrossing Shoal Creek at the Savannah Ford, and went into camp at Hains’ plantation, three miles from Cowpen Mills.” (The Confederate infantry lines were at Wilson’s Crossroads–today’s St. Florian. Coons doesn’t make communication with the troops in Waynesboro. Hatch expected them to be near the Butler creeks–those troops in Waynesboro covering the area from there to the west bank of Shoal Creek. It isn’t clear if he’s OK with Coon moving back to the east side of Shoal Creek.)

“November 18, made reconnaissance across Shoal Creek with the entire brigade three miles to Butler Creek and Florence road (County Road 61), and sent the Second Iowa Cavalry as patrols to the Florence and Waynesborough road (to present-day Chisholm Road near Zip City, via County Road 8), entering that road four miles distant, returned to Cowpen Mills and camped.” (Apparently, due to the activity the two days prior, the Confederate pickets withdrew further south from the county roads 8 & 61 crossroads.

Thomas continues to be unhappy that his two cavalry commands are still not communicating. Hatch will order Coon again to cross the creek, camp & establish a picket line north of Confederate positions west of Shoal Creek and potentially link up with the troops in Waynesboro. It appears in hindsight that Hatch expected those troops to move towards him, which never happened.)

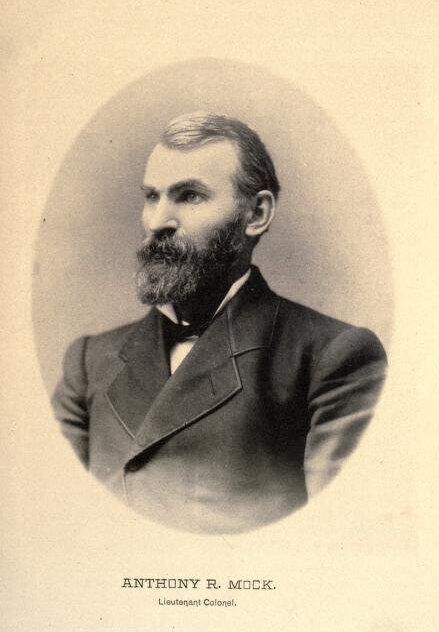

“November 19, in compliance with orders from division commander, moved my brigade across Shoal Creek at Cowpen Ford, for the purpose of camping on Butler Creek. – On reaching the Butler Creek road, three miles west, drove in the enemy’s picket, and sent Capt. A. B. Mock, of Ninth Illinois Cavalry, commanding battalion, to patrol the Waynesborough road. The main column turned north to Butler’s Creek, while Capt. J. W. Harper, with the remainder of his regiment (the Ninth Illinois Cavalry), stood picket on the road running south toward Florence. I remained with my escort at the cross-roads to see the train safely closed up for three-quarters of an hour, when I was informed by an orderly that the Second Iowa had met the enemy in heavy force, and that Buford’s division was in their front, on Big Butler Creek. At about this moment Captain Harper reported the enemy pressing his picket from the south, and that they had the appearance of being infantry. Leaving an orderly to close the column I sent another to inform Captain Harper that he must hold his position at all hazards until the pack train and artillery had passed, as it was impossible, from the bad condition of the road, to halt or return by the same route. I then rode rapidly to the Second Iowa, and found them engaged with a superior force. I immediately sent the train and artillery down the valley of the Little Butler, accompanied by the Sixth Illinois as escort, Major Whitsit commanding, who was instructed to take all axes and spades and make a crossing on Shoal Creek at all hazards, as this was the only place of escape from a well devised trap of the enemy. The next thirty minutes were passed in great anxiety, as Buford, on the north, was pressing the Second Iowa hard in front and flanking on their right and left with vastly superior numbers, while the Ninth Illinois was heavily pressed in the rear by a force from the south. During this time a messenger was sent to Captain Mock, informing him of his situation, and that unless he returned soon I would be compelled to abandon the last place left for his escape. As the Ninth Illinois came up they passed to the right and rear of the Second Iowa, down the Little Butler, and forming a line dismounted at the junction of the Big and Little Butler, where the high and abrupt bluffs on either side made the valley quite narrow. This made a good support for the Second Iowa when compelled to fall back. By this time the situation of the Second Iowa became truly critical, in consequence of the rapid movements of the rebel flanking column, which reached nearly to their rear on the right and left. Seeing it was impossible to hold the gap until Captain Mock could be heard from I ordered Major Horton to fall back and form again in rear of the Ninth Illinois. Each regiment then fell back alternately and formed lines for two miles, when we reached Shoal Creek, and I found, to my great surprise, the Sixth Illinois pack train, artillery, and ambulances all safe on the opposite side, and the regiment dismounted to cover the crossing. A lively skirmish was kept up by the rear guard while the command passed down the steep miry bank by file obliquely 150 feet. The mortification and apparent chagrin of the rebels when they found their prey had unexpectedly escaped was made known by those hideous yells, such as only rebels can make. I carefully placed my pickets on all practicable roads and encamped at dark at the same place I had left in the morning, with the firm conclusion, as previously reported, that Butler’s Creek was by no means a desirable location to encamp. The day had been one of incessant rain.”

Interesting story–one that isn’t well known in Lauderdale County. The Federal troops had definitely gotten in a trap, although it of their own doing as the Confederates hadn’t planned anything. Confederate troops under Gen. Abraham Buford had moved their camp northeastward to be ready for the upcoming campaign northward. One of Buford’s Kentucky brigades was foraging near the Pruitton area when the 2nd Iowa Cavalry came upon them, leading to a firefight. Naturally, Buford’s troops rallied to the firing & soon outnumbered the Iowans. The Iowans were armed with Spencer repeating rifles, so they were able to hold their own & gave up ground slowly. In this action Col. Edward Crossland, commanding the Kentuckians, was severely wounded and would not participate in the upcoming Tennessee campaign.

Also advancing that day, north on the Butler Creek Road, was Gen. Frank Armstrong’s Confederate cavalry brigade. He ran headlong into the Yankee troops just south of the county roads 8 & 62 crossroads.

Neither Confederate general realized the predicament that the Yankee troopers were in nor understood the terrain. Forrest, their commander, was miles away & perhaps still in Florence. Had it actually been a trap, the outcome would have been much bloodier & perhaps as dire as Coon’s report stated. There was a road leading directly to Coon’s rear from the south. Its use would have been disastrous for his command.

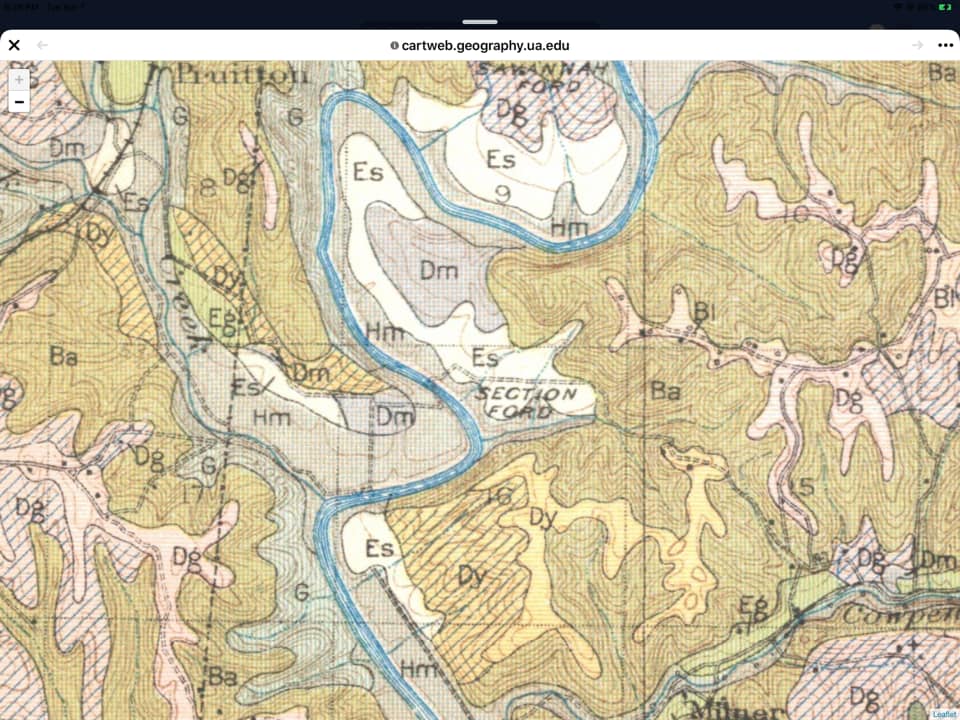

Oh, I almost forgot–the ford does have a name. Or, at least, it had a name for a short while. It’s called Section Ford & you can see it on a 1930s-era agricultural map. Go figure.

Photo details:

- Topographical map (third photo, above, right) depicts area described in Coon’s report. Butler Creek, Little Butler Creek, Pruitton, Goose Shoals, Cowpen Creek, Savannah Ford & Shoal Creek are labeled. County Road 8 crosses Shoals Creek at Goose Shoals Bridge & meets the Butler Creek Road (County Road 61) at the crossroads at the center left edge of map. Coon’s troops made a fighting withdrawal from the Butler Creek Road down the Butler Creek Valley, northwest to southeast, finally crossing at a hidden ford. (Section Ford is not labeled on this map.) County Road 302 parallels the Butler Creek road & ends at Butler Creek. Although not labeled, it leaves County Road 8 halfway between the section 17 & 18 numbers on the map. It runs northeastward to the creek.

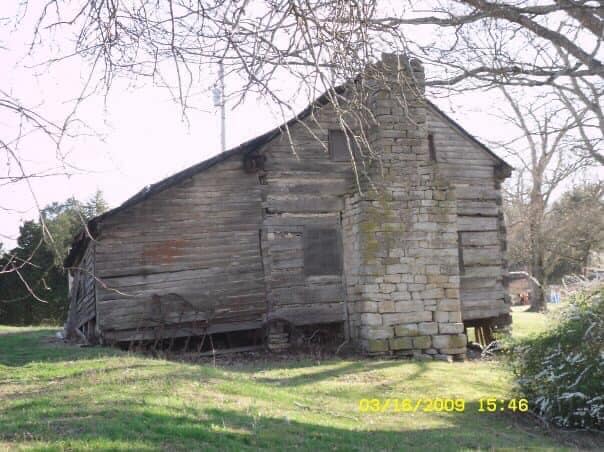

- The Hugh Riah Reynolds house (fourth photo, above, right) was built in 1824. It is on County Road. The road from this house to the Butler Creek bottoms would have led to the Union rear–a much shorter distance to the battle for Armstrong’s Confederates. According to the Bugger Saga, Forrest slept here on his way north to his engagement with Hatch at Lawrenceburg. One of Reynolds’ sons, Capt. J.M. Reynolds, commanded Company B of Biffle’s 9th TennesseeCavalry. This unit was in the Waynesboro area at the time, opposing the Union troopers there. Reynolds’ company had a number of soldiers whose homes were in this area. Obviously, they would have known about this road and the hidden ford.

- 1931 USDA soils map (right) shows Section Ford, which is the “hidden ford.” It also shows the potential routes to the Union rear, unknown to the Confederates. The Union line started a withdrawal down the Butler Creek valley to Shoal Creek, both flanks anchored on the high ground.

Blog-post author Greg Gresham is doing stuff he likes to do after retiring from 33 years in the pulp & paper industry. When he’s not golfing or enjoying being a grandfather, he digs into historical research with an emphasis on Civil War era local history. Sometimes he stumbles on intriguing yarns from years ago, or–with a little luck–he solves a mystery or two. Those, he says, make good stories.