By Ashley Steenson

PhD candidate, History Dissertation Fellow

University of Alabama

Drafted in 1933 and first explained in a message to Congress by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Tennessee Valley Authority Act is one of the most radical pieces of legislation in U.S. history, along with the Glass-Steagall Act from the same year and the Social Security Act of 1935. While the TVA marked the first time the U.S. government took over the economic development of an entire region’s resources, the aristocratic backgrounds of the TVA’s supporters were often a far cry from those of the people it helped and the little towns they left behind.

Born in 1894 to a Montgomery surgeon and mother from Mobile, J. Lister Hill went to The University of Alabama at 16. Hill helped to build the Alabama chapter of Theta Nu Epsilon, informally known as the ‘the Machine.’ He would go on to earn one law degree from Alabama and another from Columbia University, serving 15 years in the U.S. House of Representatives and later as a U.S. senator.

Hill was a Southern gentleman in the old style, with Mississippi writer David Cohn documenting his interests in 1944 for The Atlantic: “Aside from fishing and hunting, Hill likes to take long walks in the woods with his retriever spaniel and attend the theater.” He was “an addict of five-cent candy bars, Walt Whitman, … military affairs, The Federalist, English poetry, [and] Thomas Jefferson.” [i]

Like towering Alabama liberals Hugo Black and John Bankhead Jr., Hill knew how to get what he wanted and quickly became one of President Roosevelt’s trusted advisers. An opponent of civil rights, Hill personified “the aristocrat as Democrat” and was a champion of economically progressive causes. [ii] He sponsored the Hill-Burton Hospital Act of 1946 that built thousands of medical facilities in rural and poor areas, and an Alabama newspaper portrayed Hill’s election victory as a win “for the New Deal, Rooseveltism, democracy, [and] the WPA.” [iii] [iv]

Named after acclaimed English surgeon Baron Joseph Lister, Hill was “much nearer to the great eighteenth-century Southerners, who were at once revolutionaries and builders, than he is to many contemporaries in his region.” Hill’s liberalism emphasized individual freedom, scientific progress, and social reform. As such, he secured his place in history when he became the House sponsor of the unprecedented Tennessee Valley Authority legislation of 1933. The economic landscape of Hill’s resource-rich home state was then largely determined by corporations such as the Alabama Power Company. [v]

Thanks to Hill and Senator George Norris of Nebraska, the federal government harnessed the power of the Tennessee River to produce hydroelectric power for north Alabama and the entire Tennessee River Valley. FDR signed the TVA in 1933 to accomplish this and also assist with flood control and afforestation, prevent soil erosion, support national defense, develop better fertilizers, and aid navigation through the dangerous, rocky shoals of northwest Alabama. [vi]

It meant the reinvention of a region and a people defined by poverty, but that reinvention came at a price some weren’t willing to pay. The TVA, this revolutionary legislation backed by a visionary from Nebraska and an enlightened south Alabama son of privilege, spelled the end for little towns across the valley. One of those towns was Riverton, Alabama.

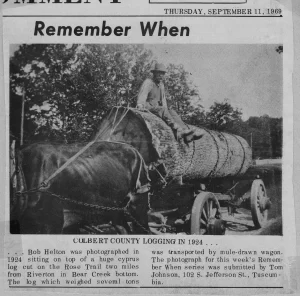

While Scott Fitzgerald finished The Great Gatsby — an ode to newly accessible electricity — in Paris in 1924, and over 20 years after writer Henry Adams’ poetic tribute to electric power, many in Riverton used fireplaces to heat their homes. A decade after Lister Hill read the classics at Alabama, men still cut and mules still pulled the ancient cypresses from the river bottom to the heart of town. [vii] Riverton had no telephones or electric connections. Only a few of the 36 families had indoor plumbing, which caused disease to spread. A fifth of nearby Waterloo’s residents would die of malaria between 1934 and 1935. [viii]

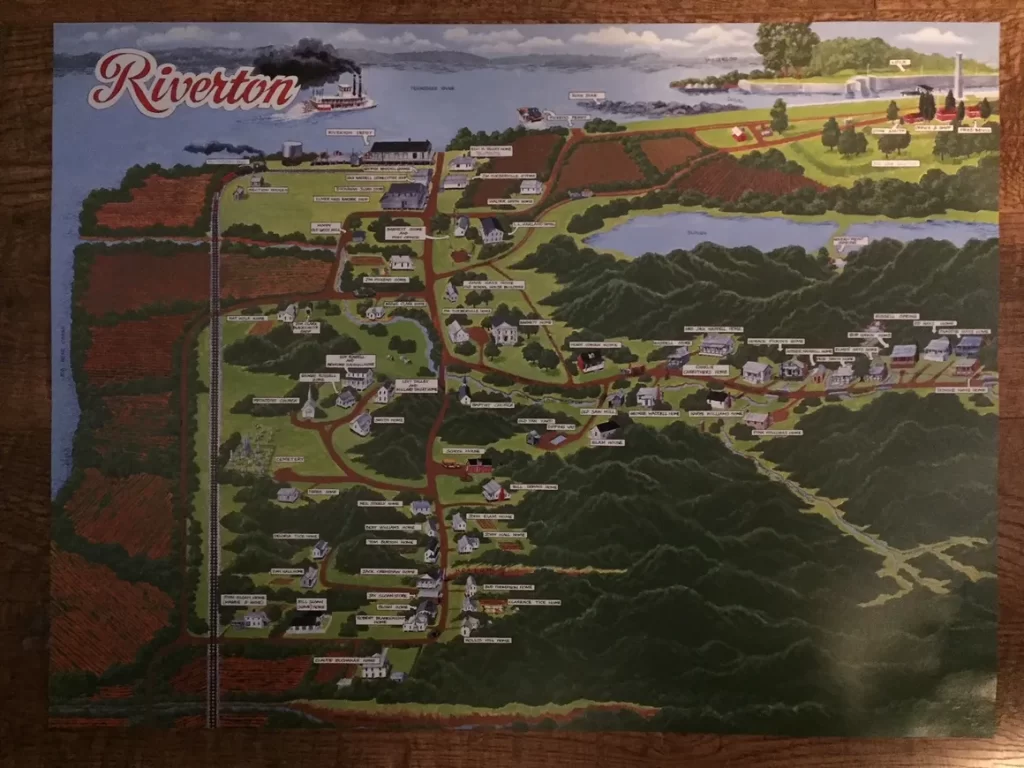

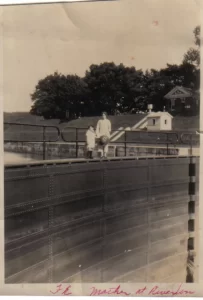

Riverton was founded in 1887 when a Philadelphia businessman with British investors bought the former town of Chickasaw and began construction on a railroad line. [ix] The unincorporated village had a post office, depot, hotel, and two stores, its buildings were made of wood and built around the end of the nineteenth century. [x] While many people worked in farming or logging, some were employed at the Riverton Lock, which was completed in 1911 to help boats avoid the shoals. Showing how regional problems influence national policy, issues such as the difficult passage through the Colbert and Bee Tree Shoals directly led to TVA’s creation. [xi] As a whole, around three-fourths of Riverton was on government relief, and TVA found that 86% of residents would have to seek new employment after Riverton was flooded. [xii]

All of this would change when Riverton disappeared from the map in 1938 with the closing of the Pickwick Landing Dam. Pickwick Landing, in Hardin County, Tennessee, is a small community named after Charles Dickens’ 1837 novel The Pickwick Papers. [xiii] Though the Pickwick Landing Dam was not the first to be built under the Roosevelt administration, it was the first to be designed by TVA. [xiv] Construction started in late 1934, and the dam was officially completed on February 8, 1938. [xv]

Alabama Polytechnic, now Auburn University, worked with extension services to relocate the residents of Riverton and Waterloo. One family from Riverton moved a few miles away and prospered with the help of the government, and a resident of a Tennessee River mussel shell camp decided to go to Arkansas. [xvi] Sarah Davenport, a Black woman who owned her home in Waterloo, looked forward to moving for better financial prospects. [xvii]

And, as the Tennessee commissioner of conservation explained at its grand unveiling, Pickwick Lake is now one of the “best motor-boat courses in America.” [xviii] In his letter suggesting TVA to Congress, FDR had claimed that Muscle Shoals’ role in World War I “leads logically to national planning for a complete river watershed involving many States and the future lives and welfare of millions,” which “touches and gives life to all forms of human concerns.” [xix]

While positive change is evident, at times the impersonality of the relocation can be apparent. A document noted that the Gean family from Waterloo seemed “mentally confused.” One letter from the superintendent of grave removal instructed a relative of someone buried on TVA land to fill out one form to reinter and another for the grave to be submerged. Though a Lauderdale County family had moved from reservoir property, TVA considered their relocation unresolved since they would have to move again — not to mention the father had gone to jail after a drunken assault. One elderly couple wished the government “would ‘do something’ to save the town” of Waterloo. [xx]

When it came to Black Southerners, TVA often relegated them to lower-level jobs and housing and did not always provide them access to recreation areas. One historian writes that, “Like most of the South, the TVA project workforce was segregated.” [xxi]

Two north Alabama artists would tell both sides of this story through their music. Mike Cooley, who grew up a few miles from Riverton, wrote the first song about TVA and recorded it with the Drive-By Truckers at a house in Athens, Georgia, in 1999. After his land was flooded, “Uncle Frank” famously “couldn’t read or write / So there was no note or letter found” when he took his own life. [xxii] Ten years later, then-member of the band Jason Isbell praises the change brought by TVA with his song of the same name: “Thank God for the TVA / Where Roosevelt let us all work for an honest day’s pay.” [xxiii]

Like other ghost towns, Riverton is now legendary. Some claim the remnants of the Riverton Lock are an old jail or that divers have found buildings beneath the dark, murky waters of Pickwick. Sadly, Riverton’s history is more final. When TVA constructed dams such as Norris, Wheeler, and Pickwick, structures were demolished and over 5,000 men cleared trees by bulldozer and hand. Any brush was burned. TVA explained that this was to “prevent possible clogging of penstocks, remove hidden dangers to navigation, and safeguard public health.” [xxiv] Resident Mary Thompson remembered driving her aging father around Riverton in 1938 when the dam was operational. As the water rose, he said he never thought he would see the day. [xxv]

Another legend holds that Riverton Rose Trail, a twenty-mile road hugging Pickwick, got its name from the roses planted by locals to remember their town. Rose Trail includes the only structures left from Riverton, such as cemetery monuments and the 1890 Buchanan House, but the roses are long gone. Riverton native, decorated veteran, and local author Ray Hays said the roses were paved over, pulled up, or poisoned with pesticides. If you do see roses, a resident asks that you please not dig them up. [xxvi]

An 1890 newspaper predicted that, “Riverton is a certainty, and that it will be a success is a foregoing conclusion.” [xxvii] While Riverton’s fate wasn’t certain, its significance as a benchmark of transformation was. Though most of its residents never left north Alabama, Riverton represents the great movements of the twentieth century, such as advancement in public health and the shift away from an agricultural economy. [xxviii]

Because of the tireless work of political powerhouses such as Hill and Norris as well as the resilience of hardworking people who lost their land and livelihoods, it can be hard to imagine today the level of devastation that north Alabama once endured. A TVA film from the 1930s was created for exactly this purpose. The film contrasted ruined farmsteads in Tennessee with images of recreation and industry as the narrator spoke: “The problems of the Valley are the problems of America.” He added, “Such poverty as this is not universal… but it exists and all too frequently, not only in the Tennessee Valley but throughout the length and breadth of our land.” [xxix]

Click here for a list of sources and citations.

3 Responses

Thank you so much for this research. I will incorporate much of it in my family ancestry writing.

Great work!!

I think the Riverton area is lovely 🌹

Generations of my family lived in Riverton. Williams and Carruthers. I just read about Sherman’s soldiers occupying Riverton during the Civil War and the devastation they left. It is still a beautiful rural area.