By Lee Freeman

Florence-Lauderdale Public Library,

Local History-Genealogy Department

Throughout the late 1820s and 1830s, there was pressure on the Alabama legislature to abolish slavery, with Quaker agents buying cotton that wasn’t produced by slave labor for a higher cost. There is anecdotal evidence of eight abolitionist societies in north Alabama in 1832, including one in Florence. Our late city historian Col. Bill McDonald wrote about a house in Lexington, in rural Lauderdale County, which was supposedly a stop on the Underground Railroad.

In a July 4, 1876, “Historical Address” published over several issues of the “Florence Gazette,” William B. Wood wrote that “(d)uring the Know-Nothing excitement, a newspaper was established by that party, called the American Democrat. The motto was ‘Put none but Americans on Guard.’ A fellow from New Hampshire named Wheeler was employed as editor. It was not long before he was exposed as a rank abolitionist, and as the South was then too hot a place for such characters, he left between two suns, in order to avoid a coat of tar and feathers which some of the enemy intended to bestow on him whilst the guard slept.”

“Know-Nothing” was the nickname given to the American Party, which was comprised of native-born Protestant white Americans who feared America was being overrun by German and Irish Roman Catholic immigrants. Party members believed that the immigrants’ allegiance was to the pope in Rome rather than the United States and its republican principles. Thus Know-Nothings sought to limit the political influence of Catholic immigrants to the US. The party had a brief ascendancy–when the US Congress assembled on Dec. 3, 1855, 43 representatives were avowed No-Nothings, and former US president Millard Fillmore was the No-Nothing presidential candidate in 1856.

Founded in 1843 as the nativist “Order of the Star-Spangled Banner,” the American Party was especially active between 1854 and 1856. Members were required to join a local lodge and swear an oath of secrecy not to reveal information regarding the membership or its aims. The organization got the nickname “Know-Nothing” because, when asked, members refused to talk about the party’s real aims & claimed to “know nothing.”

Many contemporaries mistrusted the party because of its radical nature, extreme secrecy & clandestine nature. However, many Know-Nothings in the North were also abolitionists, which made them even more despised politically among Southern Democrats. The party grew in numbers and in the mid-1850s shed its clandestine character & officially adopted the name “American Party.”

The year 1855 was the peak of consolidated Know-Nothing power–the next year, at its convention in Philadelphia, the party split along sectional lines over the pro-slavery platform of the Southern delegates. Swept up in the sectional strife, the American Party fizzled out after 1856 as anti-slavery members flocked to the new Republican Party & pro-slavery members defected to the Democrats. By 1859 Know-Nothings were confined mainly to the border-states. In 1860 the remnants of the American Party joined forces with the old-line Whigs to form the Constitutional Union Party, which nominated John Bell, of Tennessee, for president in 1860.

On July 18, 1854, the “Tuscumbia Enquirer” reported that “The Know-Nothings have sneaked into Alabama and are trying to see what they can do with the sound democracy of this State.” The paper noted that by that time Franklin County (Colbert County wasn’t created from Franklin until 1867) already had a Know-Nothing lodge.

Little is known of the Know-Nothing party’s activities in Florence & Lauderdale County. However, we do know the names of at least a couple of Florentines who were Know-Nothings: Florence hotelier Garrick Campbell and Ferdinand J. Sannoner, son of Roman Catholic immigrant & Florence surveyor Ferdinand Sannoner. Along with other “American boys about town,” Sannoner raised money to erect a “Liberty Pole” in September of 1856. Additionally, in one Florence election for city aldermen in 1855, a candidate was “refused and turned out of the board” because he was born in Ireland.

In July of 1855, New Hampshire native & newspaper editor Charles Wheler, assisted by a “Messr. Peters,” founded Florence’s Know-Nothing newspaper, a weekly called “The American Democrat.”

Wheler was born & raised in Concord, New Hampshire. As a young man, he went into the printer’s trade, publishing a volume of his poetry in 1851. He then got involved in politics, where he soon “proved himself an open and undisguised free-soiler and abolitionist.” From Sept. 4 to Nov. 27, 1852, Wheler published the abolitionist “Concord Tribune,” which endorsed Whig candidate & abolitionist Gen. Winfield Scott for president over the pro-slavery Democrat Franklin Pierce. In late 1852 or early 1853 Wheler supposedly absconded from Concord, leaving his debts unpaid. He settled in western Virginia, where he briefly edited “a rabid Know-Nothing paper” called the “Lewisburg Western Era.” In October of 1854, Wheler served as one of several secretaries at a railroad convention at White Sulphur Springs, Virginia. According to the “Tuscumbia Enquirer,” Wheler was in Franklin County for a couple of months in 1855 before going north to Florence, in Lauderdale County.

Noting the advent of the “American Democrat,” the “Tuscumbia Enquirer” wrote that “(t)he Know-Nothings of Lauderdale County contributed their money to establish a paper in Florence, and since it has made its appearance it has effected great good for the democratic [sic] party. It has a blue-mouth, vulgar-tongued Yankee as editor, whose early life was spent among the abolitionists . . .” There are only two extant partial issues of the American Democrat, both from September of 1856. They are on microfilm in the Florence-Lauderdale Public Library’s Local History-Genealogy Department.

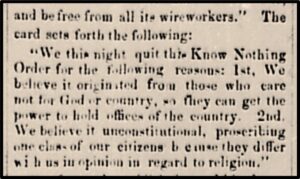

Centre Star, in east Lauderdale County, had a lodge of about 125 Know-Nothings, 40 of whom abandoned the party in late June of 1855. Deciding that the No-Nothing Order was unconstitutional due to its oath of secrecy and religious discrimination, these 40 Centre Star defectors published a “card” in the “Florence Gazette” that was reprinted by the “Tuscumbia Enquirer.” It stated part of their reason for leaving: “We believe it [the No-Nothing order] unconstitutional, proscribing one class of our citizens because they differ with us in opinion in regard to religion. . . . We oppose it upon its organization; for freemen, in a free country, to be meeting in the dark, slipping around their neighbors, for fear they might see them, denying their creed, and telling falsehoods to their best friends, to keep from violating their pledges, is enough in our opinion, within itself . . .”

Wheler came to Florence supposedly claiming to have been in the South since he was 18 years old & erroneously labelled an abolitionist for most of that time. In the Sept. 29 issue of the “American Democrat,” Wheler challenged the legality of Lauderdale County Sheriff Robert McClanahan’s 1853 appointment to that office (according to McClanahan, the problem was due to ignorance of a new law requiring sheriffs to make bond within a certain time).

On Saturday, Oct. 6, under the headline “KNOW-NOTHING EDITOR RUNAWAY,” the “Florence Gazette” reported that Wheler had “(r)unaway, strayed, absconded, surreptitiously vamosed [sic], went away, gone, by the underground-railroad.”

The Gazette insisted that it had no personal animosity against Wheler but was merely fulfilling its civic duty in order to warn other Southerners to beware of him and give him the treatment such an abolitionist deserved. The paper speculated that on Oct. 4, Wheeler had fled to Massachusetts or somewhere else where Know-Nothingism & abolitionism held sway. However, no records of Wheeler after he left Florence have been located. The “American Democrat” published for a couple more years under Maury County, Tennessee, editor John E. Hatcher before the party–and the paper–lost popularity and Hatcher returned to Tennessee.

Florence native Lee Freeman has been the local historian-genealogist at the Florence-Lauderdale Public Library since 1997. The author of one book & several articles, he serves on local historical & historical preservation boards.